Policy

Policy

If ⿻ succeeds, in a decade we imagine a transformed relationship among and across governments, private technology development and open-source/civil society. In this future, public funding (both from governments and charitable initiatives) is the primary source of financial support for fundamental digital protocols, while the provision of such protocols in turn becomes a central item on the agenda of governments and charitable actors. This infrastructure is developed trans-nationally, by civil society collaborations and standard-setting organizations supported by an international network of government leaders focused on these goals. The fabric created by these networks and the open protocols they develop, standardize, and safeguard become the foundation for a new "international rules-based order", an operating system for a transnational ⿻ society.

Making these a bit more precise opens our eyes to how different such a future could be. Today, most research and development and the overwhelming majority of software development occurs in for-profit private corporations. What little (half a percent of GDP in an average OECD country) funding is spent on research and development by governments is primarily non-digital and overwhelmingly funds "basic research." This is in contrast to open-source code and protocols that can be directly used by most citizens, civil groups, and businesses. Spending on public software R&D pales by comparison to the several percent of GDP most countries spend on physical infrastructure.

In the future, we imagine that governments and charities will ensure we devote roughly 1% of GDP to digital public research, development, protocols, and infrastructure, amounting to nearly a trillion US dollars a year globally or roughly half of current global investment in information technology. This would increase public investment by at least two orders of magnitude and, given how much volunteer investment even limited financial investment in open-source software and other public investment has been able to stimulate, completely change the character of digital industries: the "digital economy" would become a ⿻ society. Furthermore, public sector investment has primarily taken place on a national or regional (e.g. European Union) level and is largely obscured from broader publics. The investment we imagine would, like research collaborations, private investment, and open-source development, be undertaken by transnational networks aiming to create internationally interoperable applications and standards similar to today's internet protocols. It would be at least as much a focus for the public as recently hyped technologies such as AI and crypto.

As we emphasized in the previous section, ⿻ innovation does not take policy by a single government as a primary starting point: it proceeds from a variety of institutions of diverse and usually middling sizes outward. Yet governments are central institutions around the world, directing a large share of economic resources directly and shaping the allocation of much more. We cannot imagine a path to ⿻ without the participation of governments as both users of ⿻ technology and supporters of the development of ⿻.

Of course, a full such embrace would be a process, just as ⿻ is, and would eventually transform the very nature of governments. Because much of the book so far has gestured at what this would mean, in this chapter we instead focus on a vision of what might take place in the next decade to achieve the future we imagined above. While the policy directive we sketch is grounded in a variety of precedents (such as ARPA, Taiwan, and to a lesser extent India) that we have highlighted above, it does not directly follow any of the standard models employed by "great powers" today, instead drawing, combining, and extending elements from each to form a more ambitious agenda than any of these are today pursuing. To provide context, we therefore begin with a stylized description of these "models" before drawing lessons from historical models. We describe how these can be adapted to the global scope of today's transnational networks, how such investments can be financially supported and sustained, and finally the path to building the social and political support these policies will need, on which the next chapter focuses.

Digital empires

The most widely understood models of technology policy today are captured by legal scholar Anu Bradford in her Digital Empires.[1] In the US and the large fraction of the world that consumes its technology exports, technology development is dominated by a simplistic, private sector-driven, neoliberal free market model. In the People's Republic of China (PRC) and consumers of its exports, technology development is steered heavily by the state towards national goals revolving around sovereignty, development, and national security. In Europe, the primary focus has been on regulating technology imports from abroad to ensure they protect European standards of fundamental human rights, forcing others to comply with this "Brussels effect". While this trichotomy is a bit stereotyped and each jurisdiction incorporates elements of each of these strategies, the outlines are a useful foil for considering the alternative model we want to describe.

The US model has been driven by a broad trend widely documented since the 1970s for government and the civil sector to disengage from the economy and technology development, focusing instead on "welfare" and national defense functions.[2] Despite pioneering the ARPANET, the US privatized almost all further development of personal computing, operating systems, physical and social networking, and cloud infrastructure.[3] As the private monopolies predicted by J.C.R. Licklider (Lick) came to fill these spaces, US regulators primarily responded with antitrust actions that, while influencing market dynamics in a few cases (such as the Microsoft actions) were generally understood as too little too late.[4] In particular, they are understood as having allowed monopolistic dominance or tight oligopoly to emerge in the search, smartphone application, cloud services, and several operating systems markets. More recently, American antitrust regulators under the leadership of the "New Brandeis" movement have doubled down on the primary use of antitrust instruments with limited success in court and have seen the challenges of emerging monopolies only expand in the market for chips and generative foundation models.[5]

The primary rival model to the US has been the PRC, where the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has drafted a series of Five-Year plans that have increasingly in recent years directed a variety of levers of state power to invest in and shape the direction of technology development.[6] These coordinated regulatory actions, party-driven directives to domestic technology companies, and primarily government-driven investments in research and development have dramatically steered the direction of Chinese technology development in recent years away from commercial and consumer applications towards hard and physical technology, national security, chip development, and surveillance technologies. Investment that has paralleled the US, such as into large foundation models, has been tightly and directly steered by government, ensuring consistency with priorities on censorship and monitoring of dissent. A consistent crackdown on business activity not forming part of this vision has led to a dramatic fall in activity in much of the Chinese technology sector in recent years, especially around financial technology including web3.

In contrast to the US and the PRC, the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK) have (despite a few notable exceptions) primarily acted as importers of technical frameworks produced by these two geopolitical powers. The EU has tried to harness its bargaining power in that role, however, to act as a "regulatory powerhouse", intervening to protect the interests of human rights that it fears the other two powers often ignore in their race for technological supremacy. This has included setting the global standard for privacy regulation with their General Data Protection Regulation, taking the lead on the regulation of generative foundation models (GFMs) with their AI Act, and helping shape the standards for competitive marketplaces with a series of recent ex-ante competition regulations including the Digital Services Act, the Digital Markets Act and the Data Act. While these have not defined an alternative positive technological model, they have constrained and shaped the behavior of both US and Chinese firms who seek to sell into the European market. The EU also aspires to tight interoperability across the markets they serve, often leading to copycat legislation in other jurisdictions.

A road less traveled

Just as Taiwan's Yushan (Jade) Mountain rises from the intersection of the Eurasian and Pacific tectonic plates, the policy approach we surveyed in our Life of a Digital Democracy chapter from its peak arises from the intersection of the philosophies behind these three digital empires as illustrated in Figure A. From the US model, Taiwan has drawn the emphasis on a dynamic, decentralized, free, entrepreneurial ecosystem open to the world that generates scalable and exportable technologies, especially within the open-source ecosystem. From the European model, it has drawn a focus on human rights and democracy as the fundamental aspirations both for the development of basic digital public infrastructure and on which the rest of the digital ecosystem depends. From the PRC model, it has drawn the importance of public investment to proactively advance technology, steering it toward societal interests.

Together these add up to a model where the public sector's primary role is active investment and support to empower and protect privately complemented but civil society-led, technology development whose goal is proactively building a digital stack that embodies in protocols principles of human rights and democracy.

The Presidential Hackathon in Taiwan is a prime example of this unique model, blending public sector support with civil society innovation. Since its inception in 2018, this annual event has drawn thousands of social innovators and public servants, as well as teams from numerous countries, all collaborating to enhance Taiwan's ⿻ infrastructure. Each year, five outstanding teams are honored with a presidential commitment to support their initiatives in the upcoming fiscal year — elevating successful local-scale experiments to the level of national infrastructure projects.

A key feature of the Presidential Hackathon is its use of quadratic voting for public participation in selecting the top 20 teams. This elevates the event beyond mere competition, transforming it into a powerful coalition-building platform for civil society leadership. For instance, environmental groups focused on monitoring water and air pollution saw their contributions gain national prominence through the Civil IoT project — backed by a significant investment of USD $160 million — showcasing how the Taiwan model effectively amplifies the impact and reach of grassroots initiatives.

Lessons from the past

Of course, the "Taiwan model" did not emerge de novo over the last decade. Instead, as we have highlighted above, it built on the synthesis of the Taiwanese tradition of public support for cooperative enterprise and civil society (see our A View from Yushan chapter) with the model that built the internet at the United States Department of Defense's Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which we highlighted in The Lost Dao. At a moment when the US and many other advanced economies are turning away from "neoliberalism" and towards "industrial policy", the ARPA story holds crucial lessons and cautions.

On the one hand, ARPA's Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) led by Lick is perhaps the most successful example of industrial policy in American and perhaps world history. IPTO provided seed funding for the development of a network of university-based computer interaction projects at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Stanford, University of California Berkeley, Carnegie Technical Schools (now Carnegie Mellon University or CMU), and University of California Los Angeles. Among the remarkable outcomes of these investments were:

- The development of this research network into the seeds of what became the modern internet.

- The development of the groups making up this network into many of the first and still the among the most prominent computer science and computer engineering departments in the world.

- The development around these universities of the leading regional digital innovation hubs in the world, including Silicon Valley and the Boston Route 128 corridor.

Yet while these technology hubs have become the envy and aspiration of (typically unsuccessful) regional development and industrial policy around the world, it is critical to remember how fundamentally different the aspirations underpinning Lick's vision were from those of his imitators.

Where the standard goal of industrial policy is directly to achieve outcomes like the development of a Silicon Valley, this was not Lick's intention. He was instead focused on developing a vision of the future of computing grounded in human-computer symbiosis, attack-resilient networking, and the computer as a communication device. ⿻ builds closely on Lick's very much unfinished vision. Lick selected participating universities not based on an interest in regional economic development, but rather to maximize the chances of achieving his vision of the future of computing.

Industrial policy often aims at creating large-scale, industrial "nation champions" and is often viewed in contrast to antitrust and competition policies, which typically aim to constrain excessively concentrated industrial power. As Lick described in his 1980 "Computers and Government" and in contrast to both of these traditions, the IPTO effort took the rough goals of antitrust (ensuring the possibility of an open and decentralized marketplace) but applied the tools of industrial policy (active public investment) to achieve them. Rather than constraining the winners of predigital market competition, IPTO aimed to create a network infrastructure on which the digital world would play out in such a way as to avoid undue concentrations of power. It was the failure to sustain this investment through the 1970s and beyond that Lick predicted would lead to the monopolization of the critical functions of digital life by what he at the time described as "IBM" but turned out to be the dominant technology platforms of today: Microsoft, Apple, Google, Meta, Amazon, etc. Complementing this approach, rather than directly fostering the development of private, for-profit industry as most industrial policy does, Lick supported the civil society-based (primarily university-driven) development of basic infrastructure that would support the defense, government, and private sectors.[7]

While Lick's approach mostly played out at universities, given they were the central locus of the development of advanced computing at the time, it contrasted sharply with the traditional support of fundamental, curiosity-driven research of funders like the US National Science Foundation. He did not offer support for general academic investigation and research, but rather to advance a clear mission and vision: building a network of easily accessible computing machines that enabled communication and association over physical and social distance, interconnecting and sharing resources with other networks to enable scalable cooperation.

Yet while dictating this mission, Lick did not prejudge the right components to achieve it, instead establishing a network of "coopetitive" research labs, each experimenting and racing to develop prototypes of different components of these systems that could then be standardized in interaction with each other and spread across the network. Private sector collaborators played important roles in contributing to this development, including Bolt Beranek and Newman (where Lick served as Vice President just before his role at IPTO and which went on to build a number of prototype systems for the internet) and Xerox PARC (where many of the researchers Lick supported later assembled and continued their work, especially after federal funding diminished). Yet, as is standard in the development and procurement of infrastructure and public works in a city, these roles were components of an overall vision and plan developed by the networked, multi-sectoral alliance that constituted ARPANET. Contrast this with a model primarily developed and driven in the interest of private corporations, the basis for most personal computing and mobile operating systems, social networks, and cloud infrastructures.

As we have noted repeatedly above, we need not only look back to the "good old days" for ARPANET or Taiwan for inspiration. India's development of the "India Stack" has many similar characteristics.[8] More recently, the EU has been developing initiatives including European Digital Identityand Gaia-X. Jurisdictions as diverse as Brazil and Singapore have experimented successfully with similar approaches. While each of these initiatives has strengths and weaknesses, the idea that a public mission aimed at creating infrastructure that empowers decentralized innovation in collaboration with civil society and participation but not dominance from the private sector is increasingly a pattern, often labeled "digital public infrastructure" (DPI). To a large extent, we are primarily advocating for this approach to be scaled up and become the central approach to the development of global ⿻ society. Yet for this to occur, the ARPA and Taiwan models need to be updated and adjusted for this potentially dramatically increased scale and ambition.

A new ⿻ order

The key reason for an updated model is that there are basic elements of the ARPA model that are a poor fit for the shape of contemporary digital life, as Lick began realizing as early as 1980. While it was a multisectoral effort, ARPA was centered around the American military-industrial complex and its collaborators in the American academy. This made sense in the context of the 1960s, when the US was one of two major world powers, scientific funding and mission was deeply tied to its stand-off with the Soviet Union, and most digital technology was being developed in the academy. As Lick observed, however, even by the late 1970s this was already becoming a poor fit. Today's world is (as discussed above) much more multi-polar even in its development of leading DPI. The primary civil technology developers are in the open-source community, private companies dominate much of the digital world, and military applications are only one aspect of the public's vision for digital technology, which increasingly shapes every aspect of contemporary life. To adapt, a vision of ⿻ infrastructure for today must engage the public in setting the mission of technology through institutions like digital ministries, network transnationally and harness open-source technology, as well as redirect the private sector, more effectively.

Lick and the ARPANET collaborators shaped an extraordinary vision that laid the groundwork for the internet and ⿻. Yet Lick saw that this could not ground the legitimacy of his project for long; as we highlighted central to his aspirations was that "decisions about the development and exploitation of computer technology must be made not only 'in the public interest' but in the interest of giving the public itself the means to enter into the decision-making processes that will shape their future." Military technocracy cannot be the primary locus for setting the agenda if ⿻ is to achieve the legitimacy and public support necessary to make the requisite investments to center ⿻ infrastructure. Instead, we will need to harness the full suite of ⿻ technologies we have discussed above to engage transnational publics in reaching an overlapping consensus on a mission that can motivate a similarly concerted effort to IPTO's. These tools include ⿻ competence education to make every citizen feel empowered to shape the ⿻ future, cultural institutions like Japan's Miraikan that actively invite citizens into long-term technology planning, ideathons where citizens collaborate on future envisioning and are supported by governments and charities to build these visions into media that can be more broadly consumed, alignment assemblies and other augmented deliberations on the direction of technology and more.

Digital (hopefully soon, ⿻) ministries, emerging worldwide, are proving to be a more natural forum for setting visionary goals in a participatory way, surpassing traditional military hosts. A well-known example is Ukraine's Mykhailo Fedorov, the Minister of Digital Transformation since 2019. Taiwan was a forerunner in this domain as well, appointing a digital minister in 2016 and establishing a formal Ministry of Digital Affairs in 2022. Japan, recognizing the urgency of digitalization during the pandemic, founded its Digital Agency at the cabinet level in 2021, inspired by discussions with Taiwan. The EU has increasingly formalized its digital portfolio under the leadership of Executive Vice President of the European Commission for a Europe Fit for the Digital Age Margrethe Vestager, who helped inspire both the popular television series Borgen and the middle name of the daughter of one of this book's authors.[9]

These ministries, inherently collaborative, work closely with other government sectors and international bodies. In 2023, the G20 digital ministers identified DPI as a key focus for worldwide cooperation, aligning with the UN global goals.[10] In contrast to institutions like ARPA, digital ministries offer a more fitting platform for initiating international missions that involve the public and civil society. As digital challenges become central to global security, more nations are likely to appoint digital ministers, fostering an open, connected digital community.

Yet national homes for ⿻ infrastructure constitute only a few of the poles holding up its tent. There is no country today that can or should alone be the primary locus for such efforts. They must be built as at least international and probably transnational networks, just as the internet is. Digital ministers, as their positions are created, must themselves form a network that can provide international support to this work and connect nation-based nodes just as ARPANET did for university-based nodes. Many of the open-source projects participating will not themselves have a single primary national presence, spanning many jurisdictions and participating as a transnational community, to be respected on terms that will in some cases be roughly equal to those of national digital ministries. Consider, for example, the relationship of rough equality between the Ethereum community and the Taiwanese Ministry of Digital Affairs.

Exclusively high-level government-to-government relationships are severely limited by the broader state of current international relations. Many of the countries where the internet has flourished have at times had troubled relationships with other countries where it has flourished. Many civil actors have stronger transnational relationships than their governments would agree to support at an intergovernmental level, mirroring consistent historical patterns where civil connections through, for example, religion and advocacy of human rights have created a stronger foundation for cooperation than international relations alone. Technology, for better or worse, often crosses borders and boundaries of ideology more easily than treaties can be negotiated. For example, web3 communities and civic technology organizations like g0v and RadicalxChange have significant presences even in countries that are not widely understood as "democratic" in their national politics. Similar patterns at larger scales have been central to the transnational environmental, human rights, religious and other movements.[11]

While there is no necessary path from such interactions to broader democratization, it would also be an important mistake to miss the opportunity to expand the scope of interoperation in areas where it is possible while waiting for full government-to-government alignment. In her book A New World Order, leading international relations scholar Anne-Marie Slaughter sketched how such transnational policy and civil networks will increasingly complement and collaborate with governments around the world and form a fabric of transnational collaboration.[12] This fabric or network could be more effective than current international bodies like the United Nations. As such we should expect (implicit) support for these kinds of initiatives to be as important to the role of digital ministries as are their direct relationships with one another.

Some of the transnational networks that will form the key complements to digital ministries may be academic collaborations. Yet the element of the digital ecosystem most neglected by governments today is not academia, which still receives billions of dollars of research support. Instead, it is the largely ignored world of open-source and other non-profit, mission-driven technology developers. As we have extensively discussed, these already provide the backbone of much of the global technology stack. Yet they receive virtually no measurable financial support from governments and very little from charities, despite their work belonging (mostly) fully to the public domain and their being developed mostly in the public interest.

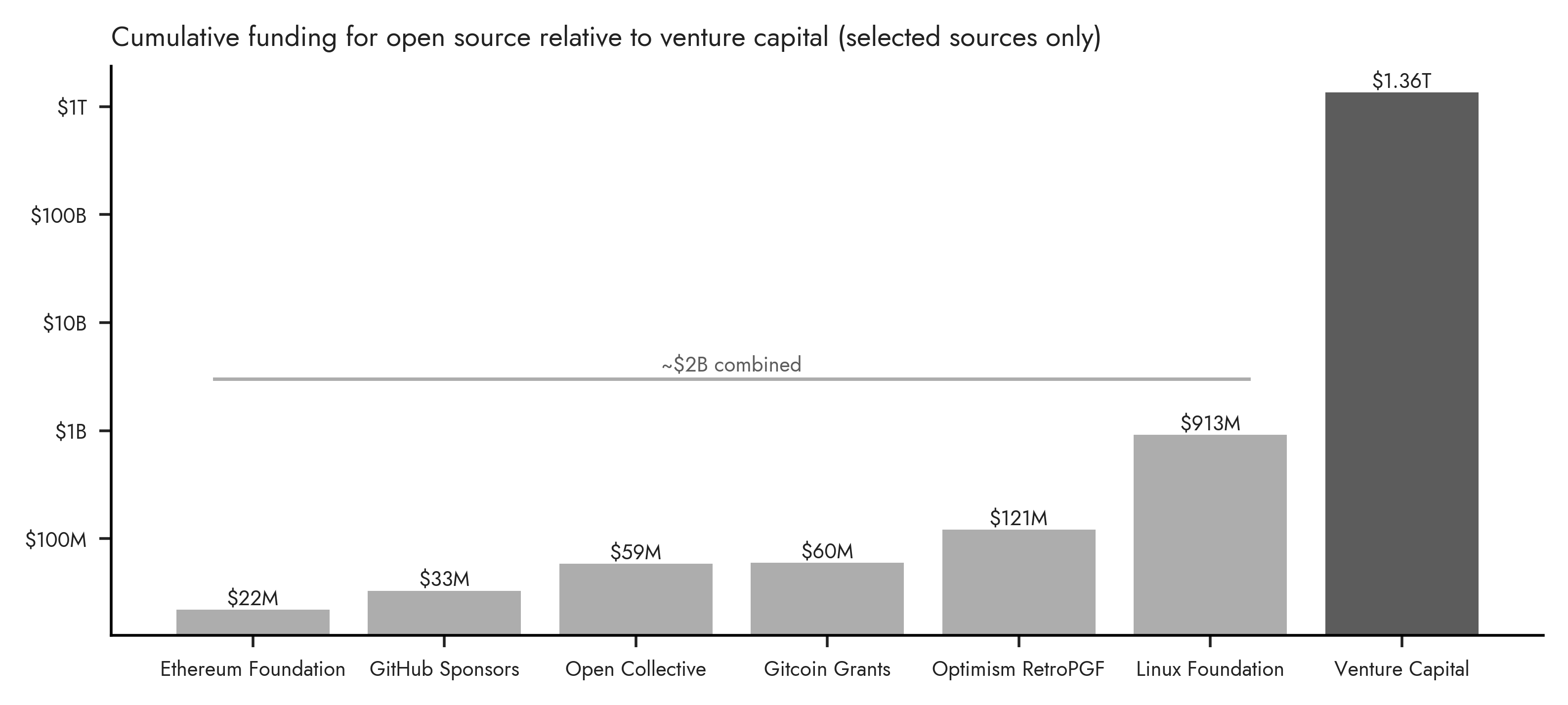

Furthermore, this sector is in many ways better suited to the development of infrastructure than academic research, much as public infrastructure in the physical world is generally not built by academia. Academic research is heavily constrained by disciplinary foci and boundaries that civil infrastructure that is broadly usable is unlikely to respect. Academic careers depend on citation, credit, and novelty in a way that is unlikely to align with the best aspirations for infrastructure, which often can and should be invisible, "boring" and as easily interoperable with (rather than "novel" in contrast to) other infrastructure as possible. Academic research often focuses on a degree and disciplinary style of rigor and persuasiveness that differs in kind from the ideal user experience. While public support for academic research is crucial and, in some areas, academic projects can contribute to ⿻ infrastructure, governments and charities should not primarily look to the academic research sector. And while academic research receives hundreds of billions of dollars in funding globally annually, open-source communities have likely received less than two billion dollars in their entire history, accounting for known sources as we illustrate in Figure B. Many of these concerns have been studied and highlighted by the "decentralized science" movement.[13]

Furthermore, open-source communities are just the tip of the iceberg in terms of what may be possible for public-interested, civil society-driven technology development. Organizations like the Mozilla and Wikimedia Foundations, while primarily interacting with and driving open-source projects, have significant development activities beyond pure open-source code development that have made their offerings much more accessible to the world. Furthermore, there is no necessary reason why public interest technology need inherit all the features of open-source code.

Some organizations developing generative foundation models, such as OpenAI and Anthropic, have legitimate concerns about simply making these models freely available but are explicitly dedicated to developing and licensing them in the public interest and are structured to not exclusively maximize profit to ensure they stay true to these missions.[15] Whether they have, given the demands of funding and the limits of their own vision, managed to be ideally true to this aspiration or not, one can certainly imagine both shaping organizations like this to ensure they can achieve this goal using ⿻ technologies and structuring public policy to ensure more organizations like this are central to the development of core ⿻ infrastructure. Other organizations may develop non-profit ⿻ infrastructure but wish to charge for elements of it (just as some highways have tolls to address congestion and maintenance) while others may have no proprietary claim but wish to ensure sensitive and private data are not just made publicly available. Fostering a ⿻ ecosystem of organizations that serve ⿻ publics including but not limited to open-source models will be critical to moving beyond the limits of the academic ARPA model. Luckily a variety of ⿻ technologies are available to policymakers to foster such an ecosystem.

Furthermore, whatever the ideal structures, it is unlikely that such public interest institutions will simply substitute for the large, private digital infrastructure built up over the last decades. Many social networks, cloud infrastructures, single-sign-on architectures, and so forth would be wasteful to simply scrap. Instead, it likely makes sense to harness these investments towards the public interest by pairing public investment with agreements to shift governance to respect public input in much the way we discussed in our chapters on Voting, Media, and Workplace. This closely resembles the way that a previous wave of economic democracy reform with which Dewey was closely associated did not simply out-compete privately created power generation, but instead sought to bring them under a network of partially local democratic control through utility boards. Many leaders in the tech world refer to their platforms as "utilities", "infrastructure" or "public squares"; it stands to reason that part of a program of ⿻ digital infrastructure will be reforming them so they truly act as such.

Fostering a ⿻ ecosystem of organizations that serve ⿻ publics including but not limited to open-source models will be critical to moving beyond the limits of the academic ARPA model. Luckily a variety of ⿻ technologies are available to policymakers to foster such an ecosystem.

⿻ regulation

To allow the flourishing of such an ecosystem will depend on reorienting legal, regulatory, and financial systems to empower these types of organizations. Tax revenue will need to be raised, ideally in ways that are not only consistent with but actually promote ⿻ directly, to make them socially and financially sustainable.

The most important role for governments and intergovernmental networks will arguably be one of coordination and standardization. Governments, being the largest actor in most national economies, can shape the behavior of the entire digital ecosystem based on what standards they adopt, what entities they purchase from and the way they structure citizens' interactions with public services. This is the core, for example, of how the India Stack became so central to the private sector, which followed the lead of the public sector and thus the civil projects they supported.

Yet laws are also at the center of defining what types of structures can exist, what privileges they have and how rights are divided between different entities. Open-source organizations now struggle as they aim to maintain simultaneously their non-profit orientation and an international presence. Organizations like the Open Collective Foundation were created almost exclusively for the purpose of allowing them to do so and helped support this project, but despite taking a substantial cut of project revenues was unable to sustain itself and thus is in the process of dissolving as of this writing. The competitive disadvantage of Third-Sector technology providers could hardly be starker.[16] Many other forms of innovative, democratic, transnational organization, like Distributed Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) constantly run into legal barriers that only a few jurisdictions like the State of Wyoming have just begun to address. While some of the reasons for these are legitimate (to avoid financial scams, etc.), much more work is needed to establish legal frameworks that support and defend transnational democratic non-profit organizational forms.

Other organizational forms likely need even further support. Data coalitions that aim to collectively protect the data rights of creators or those with relevantly collective data interests, as we discussed in our Property and Contract chapter, will need protection similar to unions and other collective bargaining organizations that they not only do not have at present but which many jurisdictions (like the EU) may effectively prevent them from having, given their extreme emphasis on individual rights in data. Just as labor law evolved to empower collective bargaining for workers, the law will have to evolve to allow data workers to collectively exercise their rights in order to avoid either their being disadvantaged relative to concentrated model builders or so disparate as to offer insuperable barriers to ambitious data collaboration.

Beyond organizational forms, legal and regulatory changes will be critical to empowering a fair and productive use of data for shared goals. Traditional intellectual property regimes are highly rigid, focused on the degree of "transformativeness" of a use that risk either subjecting all model development to severe and unworkable limitations or depriving creators of the moral and financial rights they need to sustain their work that is so critical to the function of these models. New standards need to be developed by judges, legislators, and regulators in close collaboration with technologists and publics that account for the complex and partial way in which a variety of data informs the output of models and ensures that the associated value is "back-propagated" to the data creators just as it is to the intermediate data created within the models in the process of training them.[17] New rules like these will build on the reforms to property rights that empowered the re-purposing of radio spectrum and should be developed for a variety of other digital assets as we discussed in our Property and Contract chapter.

Furthermore, if properly concerted with such a vision, antitrust laws, competition rules, interoperability mandates, and financial regulations have an important role to play in encouraging the emergence of new organizational forms and the adaptation of existing ones. Antitrust and competition law is intended to ensure concentrated commercial interests cannot abuse the power they accumulate over customers, suppliers, and workers. Giving direct control over a firm to these counterparties is a natural way to achieve this objective without the usual downsides in competition policy of inhibiting scaled collaboration. ⿻ technologies offer natural means to instantiate meaningful voice for these stakeholders as we discussed in the Workplace chapter. It would be natural for antitrust authorities to increasingly consider mandating such governance reforms as alternative remedies to anticompetitive conduct or mergers and to consider governance representation as a mitigating factor in evaluating the necessity of punitive action.[18]

Mandating interoperability, in cooperation with standard-setting processes that develop the meaning and shape of these standards, is a critical lever to make such standards workable and avoid dominance by an illegitimate private monopoly. Financial regulations help define what kinds of governance are acceptable in various jurisdictions and have unfortunately, especially in the US and UK, weighed heavily towards damaging and monopolistic one-share-one-vote rules. Financial regulatory reform should encourage experimentation with more inclusive governance systems such as Quadratic and other ⿻ voting forms that account for and address concentrations of power continuously, rather than offsetting the tendencies of one-share-one-vote to raiding with bespoke provisions like "poison pills".[19] They should also accommodate and support worker, supplier, environmental counterparty, and customer voice and steer concentrated asset holders who might otherwise have systemic monopolistic effects towards employing similar tools.

⿻ taxes

However, rules, laws, and regulations can only offer support to positive frameworks that arise from investment, innovation, and development. Without those to complement, they will always be on the defense, playing catch up to a world defined by private innovation. Thus, public and multisectoral investment is the core they must complement and making such investments obviously requires revenue, thus naturally raising the question of how it can be raised to make ⿻ infrastructure self-sustaining. While directly charging for services largely reverts to the traps of the private sector, relying primarily on "general revenue" is unlikely to be sustainable or legitimate. Furthermore, there are many cases where taxes can themselves help encourage ⿻. It is to taxes of this sort that we now turn our attention.

The digital sector has proven one of the most challenging to tax because many of the relevant sources of value are created in a geographically ambiguous way or are otherwise intangible. For example, data and networks of collaboration and know-how among employees at companies, often spanning national borders, can often be booked in countries with low corporate tax rates even if they mostly occur in jurisdictions with higher rates. Many free services come with an implicit bargain of surveillance, leading neither the service nor the implicit labor to be taxed as it would be if this price were explicit. While recent reforms to create a minimum corporate tax rate agreed by the G20 and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development are likely to help, they are not tightly adaptive to the digital environment and thus will likely only partly address the challenge.

Yet while from one side these present a challenge, on the other hand they offer an opportunity for taxes to be raised in an explicitly transnational way that can accrue to supporting ⿻ infrastructure rather than, in a fairly arbitrary way, to wherever the corporation may choose to domicile. Ideally, such taxes should aim to satisfy as fully as possible several criteria:

- Directly ⿻ (D⿻): Digital taxes should ideally not merely raise revenue, but directly encourage or enact ⿻ aims themselves.[20] This ensures that the taxes are not a drag on the system, but part of the solution.

- Jurisdictional alignment (JA): The jurisdictional network in which taxes are and can naturally be raised should correspond to the jurisdiction that disposes of these taxes. This ensures that the coalition required to enact the taxes is similar to that required to establish the cooperation that disposes of the revenue.

- Revenue alignment (RA): The sources of revenue should correspond to the value generated by the shared value created by using the revenue, ensuring that those disposing of the revenue have a natural interest in the success of their mission. It also ensures that those who pay for the tax generally benefit from the goods created with it, lessening political opposition to the tax.

- Financial adequacy (FA): The tax should be sufficient to fund the required investment.

The principle of "circular investment" that we described in our Social Markets chapter suggests that eventually they can all be generally jointly satisfied. The value created by supermodular shared goods eventually must accrue somewhere with submodular returns, which can and should be recycled back to support those values' sources. Extracting this value can generally be done in a way that reduces market power and thus actually encourages assets to be more fully used.

Despite this theoretical ideal, in practice identifying practicable taxes to achieve it is likely to be as much a process of technological trial and error as any of the technological challenges we discuss in the Democracy part of the book. Yet there are a number of promising recent proposals that seem plausibly close to fulfilling many of these objectives as we iterate further:

- Concentrated computational asset tax: Application of a progressive (either in rate or by giving a generous exemption) common ownership tax to digital assets such as computation, storage, and some kinds of data.[21]

- Digital land tax: Taxing the commercialization or holding of scarce digital space, including taxes on online advertising, holding of spectrum licenses and web address space in a more competitive way and, eventually, taxing exclusive spaces in virtual worlds.[22]

- Implicit data/attention exchange tax: Taxes on implicit data or attention exchanges involved in "free" services online, which would otherwise typically accrue labor and value-added taxes.

- Digital asset taxes: Common ownership taxes on pure-digital assets, such as digital currencies, utility tokens, and non-fungible tokens.

- Commons-derived data tax: Profits earned from models trained on unlicensed, commons-derived data could be taxed.

- Flexible/gig work taxes: Profits of companies that primarily employ "gig workers" and thus avoid many of the burdens of traditional labor law could be taxed.[23]

While a much more detailed policy analysis would be needed to comprehensively "score" these taxes according to our criteria above, a few illustrations will hopefully illustrate the design thinking pattern behind these suggestions. A concentrated computational asset tax aims simultaneously to encourage more complete use of digital assets (as any common ownership tax will), deter concentrated cloud ownership (thus increasing competition while decreasing potential security threats), and to drag on the incentives for accumulating the kind of computational resources that may allow training of potentially dangerous-scale models outside public oversight, all instantiating D⿻. Most forms of digital land tax would naturally accrue not to any nation-state, but to the transnational entities that support internet infrastructure, access and content achieving JA. An implicit data exchange tax would provide a clearer signal of the true value being created in digital economies and encourage infrastructure facilitating this to maximize that value, achieving RA.

Of course, these are just the first suggestions and much more analysis and imagination will help expand the space of possibilities. However, given that these examples line up fairly closely with the primary business models in today's digital world (viz. cloud, advertising, digital asset sales, etc.) it seems plausible that, with a bit of elaboration, they could be used to raise a significant fraction of value flowing through that world and thus achieve the FA necessary to support a scale of investment that would fundamentally transform the digital economy.

While this may seem a political non-starter, an illuminating precedent is the gas tax in the US, which while initially opposed by the trucking industry was eventually embraced by that industry when policymakers agreed to set aside the funds to support the building of road infrastructure.[24] Though the tax obviously put a direct drain on the industry, its indirect support for the building of roads was seen to more than offset this by providing the substrate truckers needed for their work. Some would, rightly, object that there may have been even better-targeted taxes for this purpose (such as road congestion charges), but gas taxes also carried ancillary benefits in discouraging pollution and were generally well-targeted at the primary users of roads at a time when charging for congestion might have been costly.

It is just possible to imagine assembling today an appropriate coalition of businesses and governments to support such an ambitious set of digital infrastructure supporting taxes. Doing so would require correct set-asides of raised funds, more clever tax instruments harnessing the abundant data online, sophisticated, and low friction means of collecting taxes, careful harnessing of appropriate but not universal jurisdictions to impose and collect the taxes in a way that cajoles others to follow along and, of course, a good deal of public support and pressure as we discuss below. Effective policy leadership and public mobilization should, hopefully, be able to achieve these and create the conditions for supporting ⿻ infrastructure.

Sustaining our future

To embody ⿻, the network of organizations that are supported by such resources cannot be a de novo monolithic global government. Instead, it must be ⿻ itself both in its structure and in its connection to existing fora to realize the commitments of ⿻ to uplift diversity and collective cooperation. While we aspire to basically transform the character of digital society, we cannot achieve ⿻ if we seek to tear down or undermine existing institutions. Our aim should be, quite the reverse, to see the building of fundamental ⿻ infrastructure as a platform that can allow the digital pie to dramatically expand and diversify, lifting as many boats as possible while also expanding the space for experimentation and growth.

Different elements of our vision require very different degrees of government engagement. Many of the most intimate technologies, for example, such as immersive shared reality intend to operate at relatively intimate scales and thus should be naturally developed in a relatively "private" way (both in funding models and in data structures), with some degree of public support and regulation steering them away from potential pitfalls. The most ambitious reforms to the structure of markets, on the other hand, will require reshaping basic governmental and legal structures, in many cases cutting across national boundaries. Development of the fundamental protocols on which all of this work rests will require perhaps the greatest degree of coordination but also a great deal of experimentation, fully harnessing the ARPA coopetitive structure as nodes in the network (such as India and Taiwan) compete to export their frameworks into global standards. An effective fabric of ⿻ law, regulation, investment, and control rights will, as much as possible, ensure the existence of a diversity of national and transnational entities capable of matching this variety of needs and deftly match taxes and legal authorities to empower these to serve their relevant roles while interoperating.

Luckily, while they are dramatically underfunded, often imperfectly coordinated, and lack the ambitious mission we have outlined here, many of the existing transnational structures for digital and internet governance have roughly these features. In short, while specific new capabilities need to be added, funding improved, networks and connections enhanced, and public engagement augmented, the internet is already, as imagined by the ARPANET founders, ⿻ in its structure and governance. More than anything, what needs to be done is build the public understanding of and engagement with this work necessary to uplift, defend, and support it.

Organizing change

Of course, achieving that is an enormous undertaking. The ideas discussed in this chapter, and throughout this book, are deeply technical and even the fairly dry discussion here barely skims the surface. Very few will deeply engage even with the ideas in this book, much less the much farther-ranging work that will need to be done both in the policy arena and far beyond it in the wide range of research, development, and deployment work that policy world will empower.

It is precisely for this reason that "policy" is just one small slice of the work required to build ⿻. For every policy leader, there will have to be dozens, probably hundreds of people building the visions they help articulate. And for each one of those, there will need to be hundreds who, while not focused on the technical concerns, share a general aversion to the default Libertarian and Technocratic directions technology might otherwise go and are broadly supportive of the vision of ⿻. They will have to understand it at more of an emotive, visceral, and/or ideological level, rather than a technical or intellectual one, and build networks of moral support, lived perspectives, and adoption for those at the core of the policy and technical landscape.

For them to do so, ⿻ will have to go far beyond a set of creative technologies and intellectual analyses. It will have to become a broadly understood cultural current and social movement, like environmentalism, AI, and crypto, grounded in a deep, both intellectual and social, body of fundamental research, developed and practiced in a diverse and organized set of enterprises and supported by organized political interests. The path there includes, but moves far beyond, policymakers to the world of activism, culture, business, and research. Thus, we conclude by calling on each of you who touches any of these worlds to join us in the project of making this a reality.

Anu Bradford, Digital Empires: The Global Battle to Regulate Technology (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2023). ↩︎

Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw, The Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy (New York: Touchstone, 2002). ↩︎

Tarnoff, op. cit. ↩︎

Licklider, "Comptuers and Government", op. cit. Thomas Philippon, The Great Reversal (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019). ↩︎

Lina Khan, "The New Brandeis Movement: America’s Antimonopoly Debate", Journal of European Competition Law and Practice 9, no. 3 (2018): 131-132. Akush Khandori, "Lina Khan's Rough Year," New York Magazine Intelligencer December 12, 2023 at https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2023/12/lina-khans-rough-year-running-the-federal-trade-commission.html. ↩︎

Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, 14th Five-Year Plan, March 2021; translation available at https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/china-14th-five-year-plan/. ↩︎

Licklider, "Computers and Government", op. cit. ↩︎

Vivek Raghavan, Sanjay Jain and Pramod Varma, "India Stack—Digital Infrastructure as Public Good", Communications of the ACM 62, no. 11: 76-81. ↩︎

Danny Hakim, "The Danish Politician Who Accused Google of Antitrust Violations", New York Times April 15, 2015. ↩︎

Benjamin Bertelsen and Ritul Gaur, "What We Can Expect for Digital Public Infrastructure in 2024", World Economic Forum Blog February 13, 2024 at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/02/dpi-digital-public-infrastructure. Especially in the developing world, many countries have ministries of planning that could naturally host or spin off such a function. ↩︎

Alexander Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999). For a recent case study of the role of religion in Middle East cooperation, see Johnnie Moore, "Evangelical Track II Diplomacy in Arab and Israeli Peacemaking", Liberty University dissertation (2024). ↩︎

Anne-Marie Slaughter, A New World Order (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). This book has a special place in one of our hearts, as obtaining a prerelease signed copy was the first birthday present one author gave to the woman who became his wife. ↩︎

Sarah Hamburg, "Call to Join the Decentralized Science Movement", Nature 600, no. 221 (2021): Correspondence at https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03642-9. ↩︎

Jessica Lord, "What's New with GitHub Sponsors", GitHub Blog, April 4, 2023 at https://github.blog/2023-04-04-whats-new-with-github-sponsors/. GitCoin impact report at https://impact.gitcoin.co/. Kevin Owocki, "Ethereum 2023 Funding Flows: Visualizing Public Goods Funding from Source to Destination" at https://practicalpluralism.github.io/. Open Collective, "Fiscal Sponsors. We need you!" Open Collective Blog March 1, 2024 at https://blog.opencollective.com/fiscal-sponsors-we-need-you/. Optimism Collective, "RetroPGF Round 3", Optimism Docs January 2024 at https://community.optimism.io/docs/governance/retropgf-3/#. ProPublica, "The Linux Foundation" at https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/460503801. ↩︎

OpenAI, "OpenAI Charter", OpenAI Blog April 9, 2018 at https://openai.com/charter. Anthropic, "The Long-Term Benefit Trust", Anthropic Blog September 19, 2023 at https://www.anthropic.com/news/the-long-term-benefit-trust. ↩︎

Open Collective Team, "Open Collective Official Statement - OCF Dissolution" February 28, 2024 at https://blog.opencollective.com/open-collective-official-statement-ocf-dissolution/. ↩︎

An interesting line of research suggesting possibility here is that of neural network and genetic algorithm pioneer John H. Holland, who tried to draw direct analogies between networks of firms in an economy linked by markets and neural networks. John H. Holland and John M. Miller, "Artificial Adaptive Agents in Economic Theory", American Economic Review 81, no. 2 (1991): 365-370. ↩︎

Hitzig et al., op. cit. ↩︎

Eric A. Posner and E. Glen Weyl, "Quadratic Voting as Efficient Corporate Governance", University of Chicago Law Review 81, no. 1 (2014): 241-272. ↩︎

Economists would refer to such taxes as "Pigouvian" taxes on "externalities". While a reasonable way to describe some of the below, as noted in our Markets chapter, externalities may be more the rule than the exception and thus we prefer this alternative formulation. For example, many of these taxes address issues of concentrated market power which do create externalities, but are not usually considered in the scope of Pigouvian taxation. ↩︎

See the ongoing work developing this idea of Charlotte Siegmann, "AI Use-Case Specific Compute Subsidies and Quotas" (2024) at https://docs.google.com/document/d/11nNPbBctIUoURfZ5FCwyLYRtpBL6xevFi8YGFbr3BBA/edit#heading=h.mr8ansm7nxr8. ↩︎

Paul Romer, "A Tax That Could Fix Big Tech", New York Times May 6, 2019 advocated related ideas. ↩︎

Gray and Suri, op. cit. ↩︎

John Chynoweth Burnham, "The Gasoline Tax and the Automobile Revolution" Mississippi Valley Historical Review 48, no. 3 (1961): 435-459. ↩︎