Augmented Deliberation

Augmented Deliberation

As we have noted above, one of the most common concerns about social media has been its tendency to entrench existing social divisions, creating "echo chambers" that undermine a sense of shared reality.[1] News feed algorithms based on "collaborative filtering" selects content that is likely to maximize user engagements, prioritizing like-minded content that reinforces users' existing beliefs and insulates them from diverse information. Despite mixed findings on whether these algorithms truly exacerbate political polarization and hamper deliberations, it is natural to ask how these systems might be redesigned with the opposite intention of “bridging” the crowd. The largest-scale attempt at this is the Community Notes (formerly Birdwatch) system in the X (formerly Twitter) social media platform.

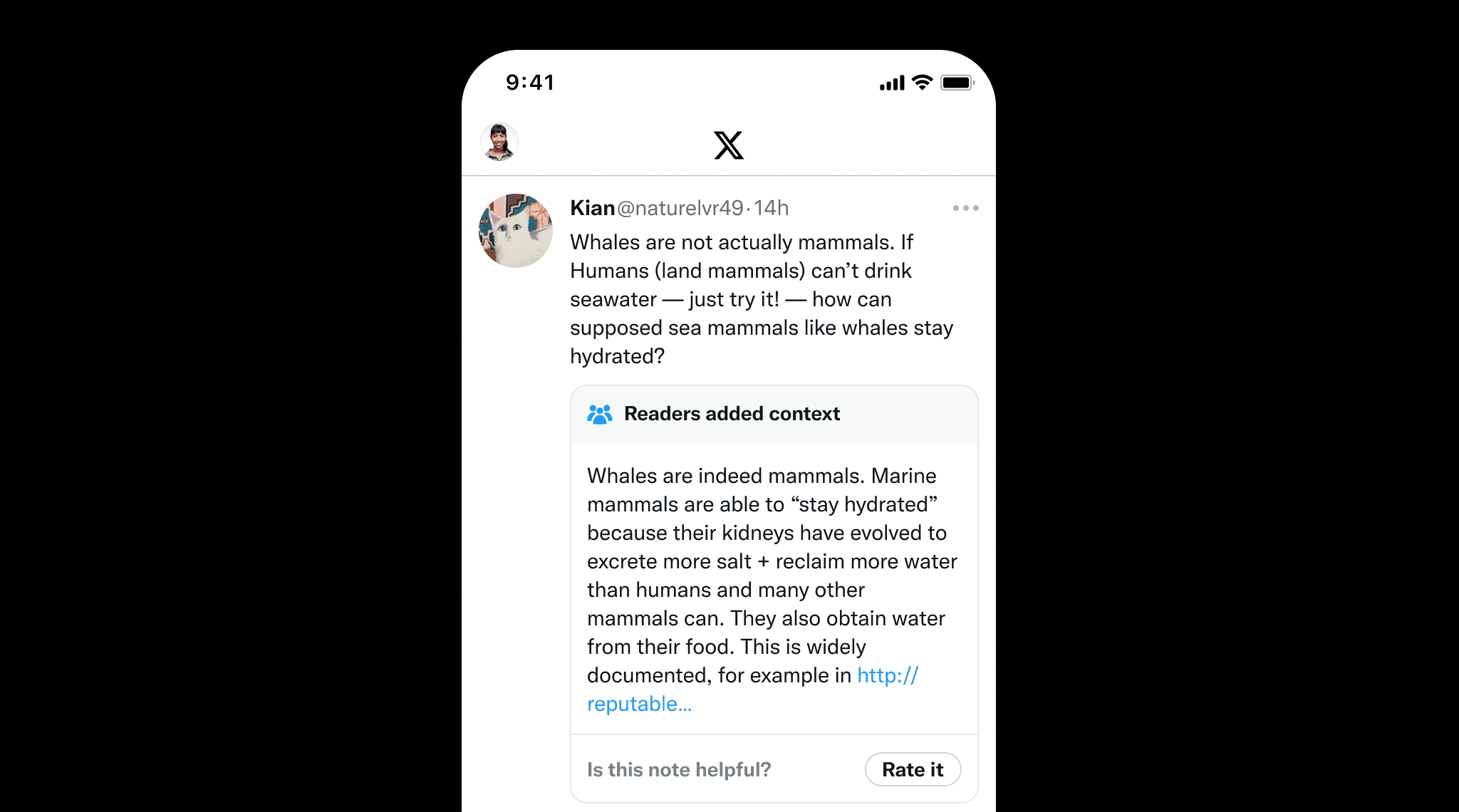

Community Notes (CN) is a community-based “fact-checking” platform. CN allows members of the X community to flag potentially misleading posts and provide additional contexts about why the posts could be misleading. CN participants not only submit these notes to the platform; they also rate the notes proposed by others. These ratings are used to assess whether the notes are helpful and are eligible to be publicly released to the X platform as illustrated in Figure A.[2]

Specifically, raters are placed on a one-dimensional spectrum of opinion, discovered by the statistical analysis from the data but in practice corresponding in most applications to the "left-right" divide in the politics of much of the Western hemisphere. Then (or really simultaneously), the support each note receives from any community member is attributed to a combination of its affinity to their position on this spectrum and some underlying, position-agnostic "objective quality". Notes are then considered to be “helpful” if this objective quality, rather than the overall ratings, is sufficiently high. Instead of prioritizing notes that are supported by a biased, like-minded cluster of users, the system rewards notes that are supported by diverse groups of users, correcting biases driven by political and social fragmentation. This approach leverages alternative social media algorithms to augment human deliberations, prioritizing contents based on the principle of collaboration across diversity, consistent with ⿻, to which hundreds of millions of people are currently exposed each week.[3] This platform has been shown to encourage the exploration of diverse political information, compared to the previous methods of moderating misinformation [4].

In this chapter, we explore the considerable power and limitations of human conversations, expressing hope that advances in ⿻ might transform conversations into a more powerful engine for both amplifying and connecting diverse perspectives in ways previously unimaginable.

Conversation today

The oldest, typically richest, and still most common form of conversations is the “in-person meeting.” Idealized portraits of democracy typically refer to discussions involved in these in-person conversations, such as what took place among traditional tribes, in the Athenian marketplaces, or in New England town halls, rather than to votes or media. The recent film, Women Talking, brilliantly captures this spirit in its portrait of a traumatized community coming to a plan for common action through discussion. Groups of friends, clubs, students and teachers, all exchange perspectives, learn, grow, and form a common purpose through in-person talk. In addition to their interactive nature, in-person interactions often carry elements of richer, non-verbal communication, as participants share a physical context and can perceive many non-verbal cues, such as facial expressions, body language, and gestures, from others in the conversation.

The next oldest and most common communicative form is writing. While far less interactive, writing enables words to travel over much greater distances and time. Typically conceived as capturing the voice of a single "author", written communications can spread broadly, even globally, with the aid of printing and translation. They can endure for thousands of years, allowing for a "broadcast" of messages much farther than amphitheaters or loudspeakers can achieve.

This underscores a crucial trade-off: the richness and immediacy of in-person discussions versus the extensive reach and permanence of the written word. Many platforms strive to blend elements of both in-person and written communication by creating a network where in-person conversations serve as links among individuals who are physically and socially proximate, and writing serves as a bridge, connecting people who are geographically distant from each other. The World Cafe [5] or Open Space Technology [6] methods allow dozens or even thousands of people to convene and participate in small groups for dialogue while the written notes from those small clusters are synthesized and distributed broadly. Other examples include constitutional and rule-making processes, book clubs, editorial boards for publications, focus groups, surveys, and other research processes. A typical pattern is that a group deliberates on writing that is then submitted to another deliberative group that results in another document that is then sent back, and so on. One might recognize this in legal tradition via oral and written arguments, as well as the academic peer review process.

One of the most fundamental challenges this variety of forms tries to navigate is the trade-off between diversity and bandwidth.[7] On the one hand, when we attempt to engage individuals with vastly diverse perspectives in conversations, the discussions could become less efficient, lengthy, costly, and time-consuming. This often means that they have trouble yielding definite and timely outcomes; resulting in the "analysis paralysis" often bemoaned in corporate settings and the complaint (sometimes attributed to Oscar Wilde) that "socialism takes too many evenings".

On the other hand, when we attempt to increase the bandwidth and efficiency of conversations, they often struggle to remain inclusive of diverse perspectives. People engaging in the conversation are often geographically dispersed, speak different languages, have different conversational norms, etc. Diversity in conversational styles, cultures and language often impedes mutual understanding. Furthermore, given that it is impossible for everyone to be heard at length, some notion of representation is necessary for conversation to cross broad social diversity, as we will discuss at length below.

Perhaps the fundamental limit on all these approaches is that while methods of broadcast (allowing many to hear a single statement) have dramatically improved, broad listening (allowing one person to thoughtfully digest a range of perspectives) remains extremely costly and time consuming.[8] As economics Nobel Laureate and computer science pioneer Herbert Simon observed, "(A) wealth of information creates a poverty of attention."[9] The cognitive limits on the amount of attention an individual can give, when trying to focus on diverse perspectives, potentially impose sharp trade-offs between diversity and bandwidth, as well as between richness and inclusion.

A number of strategies have, historically and more recently, been used to navigate these challenges at scale. Representatives are chosen for conversations by a variety of methods, including:

- Election: A campaign and voting process are used to select representatives, often based on geographic or political party groups. This is used most commonly in politics, unions and churches. It has the advantage of conferring a degree of broad participation, legitimacy and expertise, but is often rigid and expensive.

- Sortition: A set of people are chosen randomly, sometimes with checks or constraints to ensure some sort of balance across groups. This is used most commonly in focus groups, surveys and in citizen deliberative councils [10] on contentious policy issues.[11] It maintains reasonable legitimacy and flexibility at low cost, but sacrifices (or needs to supplement with) expertise and has limited participation.

- Administration: A set of people are chosen by a bureaucratic assignment procedure, based on "merit" or managerial decisions to represent different relevant perspectives or constituencies. This is used most commonly in business and professional organizations and tends to have relatively high expertise and flexibility at low cost, but has lower legitimacy and participation.

Once participants to a deliberation are selected and arrive, facilitating a meaningful interaction is an equally significant challenge and is a science unto itself. Ensuring all participants, whatever their communicative modes and styles, are able to be fully heard requires a range of social technologies and practices, including clear purpose and agenda setting, active inclusion, small group breakouts, careful management of notes (often called the “harvest” of many small group conversations), turn-taking, and encouragement of active listening and often translation and accommodation of differing abilities for auditory and visual communication styles. A very rich field of “dialogue and deliberation” research and methods have been innovated over the last 50-60 years, and the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation is a hub for exploring these.[12] These tools can help overcome the "tyranny of structurelessness" that often affects attempts at inclusive and democratic governance, where unfair informal norms and dominance hierarchies override intentions for inclusive exchange [13].

Appropriate use of digital technologies can augment the social technologies for engagement, and the intersection of the two can be fruitful. Physical travel distance used to be a severe impediment to deliberation. However, phone and video conferences have significantly mitigated this challenge, making various formats of distance/virtual meetings increasingly common venues for challenging discussions.

The rise of internet-mediated writing, including formats such as email, message boards/usenets, webpages, blogs, and notably social media, has significantly broadened “inclusion” in written communication. These platforms offer unique opportunities for individuals to gain visibility and attention easily through user interactions (e.g., "likes" or "reposts") and algorithmic ranking systems. This paradigm shift has enabled the diffusion of information among the public, a process once firmly controlled by the editorial procedures of legacy media. However, the effectiveness of these platforms in optimally distributing attention remains a topic of debate. A common drawback is the lack of context and thorough moderation in the diffusion of information, contributing to issues like the spread of "misinformation" and "disinformation," and the dominance of well-resourced entities. Moreover, the reliance on algorithmic ranking can inadvertently create "echo chambers," confining users to a narrow stream of content that reflects their existing beliefs, thus limiting their exposure to a diverse range of perspectives and knowledge.

Conversation tomorrow

Recent advancements are progressively shifting the dynamics of the trade-offs, enabling more efficient and networked sharing of rich, in-person deliberations. Simultaneously, these developments are facilitating more thoughtful, balanced, and contextualized moderation within increasingly inclusive forms of social media, thereby enhancing the overall quality and reach of these platforms.

As we discussed in The Life of a Digital Democracy chapter above, one of the most successful examples in Taiwan has been the vTaiwan system, which harnesses OSS called Polis.[14] This platform shares some features with social media services like X, but builds abstractions of some of the principles of inclusive facilitation into its attention allocation and user experience. As in X, users submit short responses to a prompt. But rather than amplifying or responding to one another's comments, they simply vote these up or down. These votes are then clustered to highlight patterns of common attitudes which form what one might call user perspectives. Representative statements that highlight these differing opinion groups' perspectives are displayed to allow users to understand key points of view, as are the perspectives that "bridge" the divisions: ones that receive assent across the lines that otherwise divide. Responding to this evolving conversation, users can offer additional perspectives that help to further bridge, articulate an existing position or draw out a new opinion group that may not yet be salient.

Polis is a prominent example of what leading ⿻ technologists Aviv Ovadya and Luke Thorburn call "collective response systems" and "bridging systems" and others call "wikisurveys".[15] Other leading examples include All Our Ideas and Remesh, which have various trade-offs in terms of user experience, degree of open source and other features. What these systems share is that they combine the participatory, open and interactive nature of social media with features that encourage thoughtful listening, an understanding of conversational dynamics and the careful emergence of an understanding of shared views and points of rough consensus. Such systems have been used to make increasingly consequential policy and design decisions, around topics such as the regulation of ride-hailing applications and the direction of some of the leading generative foundation models (GFMs).[16] In particular, working closely with the ⿻ NGO the Collective Intelligence Project (CIP), Anthropic's recently released Claude3 model, considered by many to be the current state-of-the-art in GFMs, sourced the constitution used to steer model behavior using Polis.[17] OpenAI, the other leading provider of GFMs today, also worked closely with CIP to run a grant program on "democratic inputs to AI" that dramatically accelerated research in this area and on the basis of which they are now forming a "Collective Alignment Team" to incorporate these inputs into the steering of OpenAI's models.[18]

An approach with similar goals but a bit of an opposite starting point centers in-person conversations but aims to improve the way their insights can be networked and shared. A leading example in this category is the approach developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Center for Constructive Communication in collaboration with their civil society collaborators; called Cortico. This approach and technology platform, dubbed Fora, uses a mixture of the identity and association protocols we discussed in the Freedom part of the book and natural language processing to allow recorded conversations on challenging topics to remain protected and private while surfacing insights that can travel across these conversations and spark further discussion. Community members, with permission from the speakers, lift consequential highlights up to stakeholders, such as government, policy makers or leadership within an organization. Cortico has used this technology to help inform civic processes such as the 2021 election of Michelle Wu as Boston's first Taiwanese American mayor of a major US city.[19] The act of soliciting perspectives via deep conversational data in collaboration with under-served communities imbues the effort with a legitimacy absent from faster modes of communication. Related tools, of differing degrees of sophistication, are used by organizations like StoryCorps and Braver Angels and have reached millions of people.

A third approach attempts to leverage and organize existing media content and exchanges, rather than induce participants to produce new content. This approach is closely allied to academic work on "digital humanities", which harnesses computation to understand and organize human cultural output at scale. Organizations like the Society Library collect available material from government documentation, social media, books, television etc. and organize it for citizens to highlight the contours of debate, including surfacing available facts. This practice is becoming increasingly scalable with some of the tools we describe below by harnessing digital technology to extend the tradition described above by extending the scale of deliberation by networking conversations across different venues together.

Other more experimental efforts, closely aligned with the techniques discussed in our Immersive Shared Reality chapter above, aim to enhance the depth and quality of remote deliberations, aspiring to emulate the richness and immediacy typically found in in-person interactions. A recent dramatic illustration was a conversation between Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg and leading podcast host Lex Fridman, where both were in virtual reality able to perceive minute facial expressions of the other. A less dramatic but perhaps more meaningful example was the Portals Policing Project, where cargo containers appeared in cities affected by police violence and allowed an enriched video-based exchange of experiences with such violence across physical and social distance.[20] Other promising elements include the increasing ubiquity of high-quality, low-cost and increasingly culturally aware machine translation tools and work to harness similar systems to enable people to synthesize values and find common ground building from natural language statements.

Frontiers of augmented deliberation

Some of these more ambitious experiments begin to point towards a future, especially harnessing language capabilities of GFMs to go much further towards addressing the “broad listening” problem, empowering deliberation of a quality and scale that has henceforth been hard to imagine. The internet enables collaboration at an extreme scale by reducing the possible space of collaborative actions, such as to buy/sell market transactions, and by utilizing a similar reduction in information transmission, i.e. to five star rating systems. An effective increase in our ability to transmit and digest information can result in a corresponding increase in our ability to deliberate on difficult and nuanced social issues.

One of the most obvious directions that is a subject of active development is how systems like Polis and Community Notes could be extended with modern graph theory and GFMs. The "Talk to the City" project of the AI Objectives Institute, for example, illustrates how GFMs can be used to replace a list of statements characterizing a group's views with an interactive agent one can talk to and get a sense of the perspective. Soon, it should be possible to go further, with GFMs allowing participants to move beyond limited short statements and simple up-and-down votes. Instead, they will be able to fully express themselves in reaction to the conversation. Meanwhile, the models will condense this conversation, making it legible to others who can then participate. Models could also help look for areas of rough consensus not simply based on common votes but on a natural language understanding of and response to expressed positions. A recent large-scale study highlights the positive impact of such tools in enhancing online democratic discussions. In this experiment, a GFM was used to provide real-time, evidence-based suggestions aimed at refining the quality of political discourse to each participant in the conversation [21]. The results indicated a noticeable improvement in the overall quality of conversations, fostering a more democratic, reciprocal exchange of ideas.

While most discussion of bridging systems focuses on building consensus, another powerful role is to support the regeneration of diversity and productive conflict. On the one hand, they help identify different opinion groups in ways that are not a deterministic function of historical assumptions or identities, potentially allowing these groups to find each other and organize around their perspective. On the other hand, by surfacing as representing consensus positions that have diverse support, they also create diverse opposition that can coalesce into a new conflict that does not reinforce existing divisions, potentially allowing organization around that perspective. In short, collective response systems can play just as important a role in mapping and evolving conflict dynamically as helping to navigate it productively.

In a similar spirit, one can imagine harnessing and advancing elements of the design of Community Notes to reshape social media dynamics more holistically. While the system currently lines up all opinions across the platform on a single spectrum, one can imagine mapping out a range of communities within the platform and harnessing its bridging-based approach not just to prioritize notes, but to prioritize content for attention in the first place. Furthermore, bridging can be applied at many different scales and to diverse intersecting groups, not just to the platform overall. One can imagine a future, as we highlight in our Media chapter below, where different content in a feed is highlighted as bridging and being shared among a range of communities one is a member of (a religious community, a physically local community, a political community), reinforcing context and common knowledge and action in a range of social affiliations.

Such dynamic representations of social life could also dramatically improve how we approach representation and selection of participants for deeper deliberation, such as in person or in rich immersive shared realities. With a richer accounting of relevant social differences, it may be possible to move beyond geography or simple demographics and skills as groups that need to be represented. Instead, it may be possible to increasingly use the full intersectional richness of identity as a basis for considering inclusion and representation. Constituencies defined this way could participate in elections or, instead of sortition, protocols could be devised to choose the maximally diverse committees for a deliberation by, for example, choosing a collection of participants that minimizes how marginalized from representation the most marginalized participants are based on known social connections and affiliations. Such an approach could achieve many of the benefits of sortition, administration and election simultaneously, especially if combined with some of the liquid democracy approaches that we discuss in the voting chapter below.

It may be possible to, in some cases, even more radically re-imagine the idea of representation. GFMs can be "fine-tuned" to increasingly accurately mimic the ideas and styles of individuals.[22] One can imagine training a model on the text of a community of people (as in Talk to the City) and thus, rather than representing one person's perspective, it could operate as a fairly direct collective representative, possibly as an aid, complement or check on the discretion of a person intended to represent that group. A striking real-world implementation of this concept is The Synthetic Party (Det Syntetiske Parti) of Denmark. Founded in 2022, it is officially the world’s first political party driven by artificial intelligence,[23] aiming to make generative text-to-text models genuinely democratic rather than merely populist. This synthetic party encapsulates a broad spectrum of often contradictory policies to reflect the diverse and fragmented views of unrepresented voters. The Synthetic Party—a collaboration between the "Computer Lars"-artist group of Asker Bryld Staunæs and Benjamin Asger Krog Møller, and the tech-hub MindFuture—conceptualized this initiative by investigating Denmark’s voter turnout statistics. They identified a persistent 15-20% abstention rate and correlated it with the existence of over 200 micro-parties failing to gain electoral seats.[24] By fine-tuning their GFM on data from these micro-parties, The Synthetic Party algorithmically integrates abstention rates and disenfranchised presence, hypothetically aiming to capture 20% of the voting populace, which approximates 20-36 seats in the 179-seat parliament. This creative approach to data-driven representation brings an almost alien perspective on democratic processes of inclusion and exclusion by probabilistically determining its representative seats based on voter disengagement, thus providing a channel to the discourse of abstentionist constituencies.

Most boldly, this idea could in principle extend beyond living human beings as we explore further in our Environment chapter below. In his classic We Have Never Been Modern, philosopher Bruno Latour argued tha t natural features (like rivers and forests) deserve representation in a "parliament of things."[25] The challenge, of course, is how they can speak. GFMs might offer ways to translate scientific measures of the state of these systems into a kind of "Lorax," Dr. Seuss's mythical creature who speaks for the trees and animals that cannot speak for themselves.[26] Something similar might occur for unborn future generations, as in Kim Stanley Robinson's Ministry for the Future.[27] For better or worse, such GFM-based representatives might be capable of carrying out deliberations faster than most humans can follow and might then convey summaries to human participants, allowing for deliberations that include individual humans and also allow for other styles, speeds and scales of natural language exchange.

Limits of augmented deliberation

The centrality of natural language to human interaction makes it tempting to forget its severe limitations. Words may be richer symbols than numbers, but they are as dust compared to the richness of human sensory experience, not to mention proprioception. "Words cannot capture" far more than they can. Whatever emotional truth it has, it is simply information, so it is theoretically logical that we form far deeper attention in common action and experience than in verbal exchange. Thus, however far deliberation advances, it cannot substitute for the richer forms of collaboration we have already discussed.

On the opposite side, talk takes time, even in the sophisticated versions we describe. Many decisions cannot wait for deliberation to fully run its course, especially when great social distance must be bridged, which will generally slow the process. The other approaches to collaboration we discuss below will address the need for timely decisions typical in many cases.

Many of the ways in which the slow pace of discussion can be overcome (e.g. using LLMs to conduct partially "in silico" deliberation) illustrate another important limitation of conversation: other methods are often more easily made transparent and thus broadly legitimate. The way conversations take inputs and produce outputs are hard to fully describe, whether they occur across people or in machines. In fact, one could consider inputting natural language to a machine and producing a machine dictation as just a more sophisticated, non-linear form of voting. But, in contrast to the administrative and voting rules we will discuss in the next two chapters, it might be very hard to achieve common understanding and legitimacy on how this transformation takes place and thus make it the basis for common action in the way that voting and markets often are. Thus, checks on the way deliberations occur and are observed arising from those other systems are likely to be important for a long time to come.

Furthermore, deliberation in the democratic process is also limited by the ability for humans to practically audit more capable GFMs. GFMs have also been demonstrated to adhere to instructions blindly in a way that may lead them to censor some perspectives.[28] To be properly ⿻ models mus offer a diverse array of reasonable responses, enabling them to adapt and reflect various perspectives, and ensuring they are accurately calibrated to the nuances of specific populations.

Lastly, deliberation is sometimes idealized as helping overcome divisions and reach a true "common will". Yet, while reaching points of overlapping and rough consensus is crucial for common action, so too is the regeneration of diversity and productive conflict to fuel dynamism and ensure productive inputs to future deliberations. Thus, deliberations and their balance with other modes of collaboration must always attend, as we have illustrated above, to this stimulus to productive conflict as much as it does to the resolution of conflict and the mitigation of explosive conflict.

Cass Sunstein, republic.com (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001) and #republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018). ↩︎

Vitalik Buterin, "What do I think about Community Notes?" August 16, 2023 at https://vitalik.eth.limo/general/2023/08/16/communitynotes.html. ↩︎

Stefan Wojcik, Sophie Hilgard, Nick Judd, Delia Mocanu, Stephen Ragain, M.B. Fallin Hunzaker, Keith Coleman and Jay Baxter, "Birdwatch: Crowd Wisdom and Bridging Algorithms can Inform Understanding and Reduce the Spread of Misinformation", October 27, 2022 at https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.15723. ↩︎

Junsol Kim, Zhao Wang, Haohan Shi, Hsin-Keng Ling, and James Evans, "Individual misinformation tagging reinforces echo chambers; Collective tagging does not," arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.11282 (2023), https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.11282. ↩︎

"The World Cafe", The World Café Community Foundation, last modified 2024, (https://theworldcafe.com/) ↩︎

"Open Space", Open Space World, last modified 2024, https://openspaceworld.org/wp2/ ↩︎

Sinan Aral, and Marshall Van Alstyne, "The diversity-bandwidth trade-off," American journal of sociology 117, no. 1 (2011): 90-171. ↩︎

To our knowledge, this concept of "broad listening" originates with Andrew Trask. However, we have no written reference for it with him and thus want to ensure he is credited here. ↩︎

Herbert Simon, “Designing Organizations for an Information-Rich World,” In Computers, Communications, and the Public Interest, edited by Martin Greenberger, 38–72. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1971. https://gwern.net/doc/design/1971-simon.pdf. ↩︎

A Citizen Deliberative Council (CDC) article on the Co-Intelligence Site https://www.co-intelligence.org/P-CDCs.html ↩︎

Tom Atlee, Empowering Public Wisdom (2012, Berkley, California, Evolver Editions, 2012) ↩︎

Liberating Structures (2024) has 33 methods for people to work together in liberating ways. Participedia is public participation and democratic innovations platform documenting methods and case studies. To get at the heart of the underlying patterns in good and effective processes two communities developed pattern languages 1) The Group Works: A Pattern Language for Brining Meetings and other Gatherings (2022) and 2) The Wise Democracy Pattern Language. ↩︎

Jo Freeman, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness.” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 41, no. 3-4 (2013): 231–46. https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.2013.0072. ↩︎

Christopher T. Small, Michael Bjorkegren, Lynette Shaw and Colin Megill, "Polis: Scaling Deliberation by Mapping High Dimensional Opinion Spaces" Recerca: Revista de Pensament i Analàlisi 26, no. 2 (2021): 1-26. ↩︎

Matthew J. Salganik and Karen E. C. Levy, "Wiki Surveys: Open and Quantifiable Social Data Collection" PLOS One 10, no. 5: e0123483 at https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0123483. Aviv Ovadya and Luke Thorburn, "Bridging Systems: Open Problems for Countering Destructive Divisiveness across Ranking, Recommenders, and Governance" (2023) at https://arxiv.org/abs/2301.09976. Aviv Ovadya, "'Generative CI' Through Collective Response Systems" (2023) at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2302.00672.pdf. ↩︎

Yu-Tang Hsiao, Shu-Yang Lin, Audrey Tang, Darshana Narayanan and Claudina Sarahe, "vTaiwan: An Empirical Study of Open Consultation Process in Taiwan" (2018) at https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/xyhft. ↩︎

Anthropic, "Collective Constitutional AI: Aligning a Language Model with Public Input" October 17, 2023 at https://www.anthropic.com/news/collective-constitutional-ai-aligning-a-language-model-with-public-input. ↩︎

Tyna Eloundou and Teddy Lee, "Democratic Inputs to AI Grant Program: Lessons Learned and Implementation Plans", OpenAI Blog, January 16, 2024 at https://openai.com/blog/democratic-inputs-to-ai-grant-program-update ↩︎

Meghna Irons, “Some Bostonians Feel Largely Unheard, With MIT’s ‘Real Talk’ Portal Now Public, Here’s a Chance to Really Listen,” The Boston Globe, October 21, 2021, https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/10/25/metro/some-bostonians-feel-largely-unheard-with-mits-real-talk-portal-now-public-heres-chance-really-listen/. ↩︎

Amer Bakshi, Tracey Meares and Vesla Weaver, "Portals to Politics: Perspectives on Policing from the Grassroots" (2015) at https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/upload_documents/Bakshi%20Meares%20and%20Weaver%20Portals%20to%20Politics%20Study.pdf. ↩︎

Lisa Argyle, Christopher Bail, Ethan Busby, Joshua Gubler, Thomas Howe, Christopher Rytting, Taylor Sorensen, and David Wingate, "Leveraging AI for democratic discourse: Chat interventions can improve online political conversations at scale." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, no. 41 (2023): e2311627120. ↩︎

Junsol Kim, and Byungkyu Lee, "Ai-augmented surveys: Leveraging large language models for opinion prediction in nationally representative surveys," arXiv (New York: Cornell University, November 26, 2023): https://arxiv.org/pdf/2305.09620.pdf. ↩︎

Chloe Xiang, This Danish Political Party is Led By an AI, Vice: Motherboard, 2022 ↩︎

The Synthetic Party (Denmark), Wikipedia ↩︎

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1993). ↩︎

Dr. Seuss, The Lorax (New York: Random House, 1971) ↩︎

Kim Stanley Robinson, Ministry for the Future (London: Orbit Books, 2020). ↩︎

David Glukhov, Ilia Shumailov, Yarin Gal, Nicolas Papernot, and Vardan Papyan, “LLM Censorship: A Machine Learning Challenge or a Computer Security Problem?” arXiv (New York: Cornell University, July 20, 2023): https://arxiv.org/pdf/2307.10719.pdf. ↩︎