Collaborative Technology and Democracy

Collaborative Technology and Democracy

This book was created to demonstrate ⿻ in action and as well as describe it: to show as well as tell. As such, it was created using many of the tools we describe in this section. The text was stored on and updated using the Git protocol that open source coders use to control versions of their software. The text is shared freely under a Creative Commons 0 license, implying that no rights to any content herein are reserved to the community creating it and it may be freely reused. At the time of this writing, dozens of diverse experts and citizens from every continent contributed to the writing as highlighted in our credits above and we hope many more will the continued evolution of the text after physical publication, embodying the practices we describe in our Creative Collaboration chapter.

Work was collectively prioritized and rewards determined using a "crowd-funding" approach we describe in our Social Markets chapter below. Changes to the text in future evolution will be approved collectively by the community using a mixture of the advanced voting procedures described in our ⿻ Voting chapter below and prediction markets. Contributors were recognized using a community currency and group identity tokens as we described in our Identity and Personhood and Commerce and Trust chapters above, which in turn was used in voting and prioritization of outstanding issues for the book. These priorities in turn determined the quantitative recognition received by those whose contributions addressed these challenges, an approach we have described with other as a "⿻ Management Protocol".[1] All this was recorded on a distributed ledger through an open-source protocol, GitRules, grounded on open-source participation rather than financial incentives. Contentious issues were resolved through tools we discuss in the Augmented Deliberation chapter below. The book has been translated and copy-edited by the community augmented by many of the cross-linguistic and subcultural translation tools we discuss in our Adaptive Administration chapter.

To support the financial needs of the book during the publication process, we harnessed several of the tools we describe in the Social Markets chapter. We hope to harness technologies from the Immersive Shared Reality chapter to communicate and explore the ideas from the book with audiences around the world.

For all these reasons, as you read this book you are both learning about the ideas and evaluating them on their merits and at the same time experiencing what they put into practice, can create. If you are inspired by that content, especially critically, we encourage you to contribute to the living and community managed continuations of this document and all its translations by submitting changes through a git pull request or by reaching out to one of the many contributors to become part of the community. We hope as many criticisms of this work as possible will be inspired by the open-source mantra "so fix it!"

While a human rights operating system is the foundation, the point of the system for most people is what is built on top of it. On top of the bedrock of human rights, liberal democratic societies run open societies democracies, and welfare capitalism. On top of operating systems, customers run productivity tools, games, and a range of internet-based communication media. In this chapter, we will illustrate the collaboration technologies that can be built on the foundation of ⿻ social protocols of the previous section.

While we have titled this section of the book "democracy", what we plan to describe goes well beyond many conventional descriptions of democracy as a system of governance of nations. Instead, to build ⿻ on top of fundamental social protocols, we must explore the full range of ways in which applications can facilitate collaboration and cooperation, the working of several entities (people or groups) together towards a common goal. Yet even these phrases miss something crucial that we focus on the power that working together has to create something greater than the sum of what the parts could have created separately.

Mathematically, this idea is known as "supermodularity" and captures the classic idea attributed to Aristotle that "the whole is greater than the sum of the parts".[2] An early example of the quantitative application of supermodularity is the idea of "comparative advantage", the first comprehensive description of which that we are aware of presented by the English economist David Ricardo in 1817.[3] "Comparative advantage" says, roughly, that overall welfare will be maximized when all trading partners specialize in making their most efficient product, even when some other partner can make everything more efficiently. Comparative advantage is understood as an 'economic law' stating in effect that there are guaranteed gains from diversity that can be realized through the market mechanism. This idea has been extremely influential in neoliberal economics (see Social Markets), although later iterations are more sophisticated than the Ricardian version and one need not accept the simplistic "free trade" implications to appreciate the benefits of gains from trade. Furthermore, given our emphasis on diversity, what we mean by "gains" here is context specific and need not be simplistically economic; instead, it will be defined by the norms and values of the individuals and communities coming together. Furthermore, our focus is less on people or groups per se than on the fabric running through and separating them, social difference. Thus, what we will describe in this part of the book is, most precisely, how technology can empower supermodularity across social difference or, more colloquially, "collaboration across diversity".

This chapter, which lays out the framework for the rest of this part of the book, will highlight why collaboration across diversity is such a fundamental and ambitious goal. We then define a spectrum of domains where it can be pursued based on the trade-off between depth and breadth of collaboration. Next, we highlight a framework for design in the space that navigates between the dangers of premature optimization and chaotic experimentation. Yet harnessing the potential of collaboration across diversity also holds the risk of reducing the diversity available for future collaboration. To guard against this we discuss the necessity of regenerating diversity. We round out this chapter by describing the structure followed in each subsequent chapter in this part.

Collaboration across diversity: promise and challenges

Why are we so focused on collaboration across diversity? A simple way to understand this is by analogy to energy systems. Prior to industrialism, rare encounters with powerful thermodynamic effects (such as oil fires in the ground) were met with fear and attempts to suppress these conflagrations. Yet with the advent of industrial harnessing of fossil fuels, it became more common to greet such explosions with a prospector's eye, looking to harness the potential energy that led to these explosions productively. In a world beset by conflict, we must learn to build engines that, just as in the Taiwanese example we opened with, convert the potential energy driving these conflicts into useful work. The ⿻ age must learn to harness social and informational potential energy as the industrial age did for fossil fuels and the nuclear age did for atomic energy.[4] Such an age may fulfill the prophecy of Matthew 20:16, "So the last shall be first, and the first last", as the most diverse and conflict-plagued places on earth (especially in Africa) hold arguably more potential energy than anywhere on the planet.

While novel in a certain sense, this is also one of the oldest and most universally resonant of all human ideas. All life depends on survival and reproduction, and cooperation across difference is critical to both: avoiding deadly conflict, but also reproduction that requires the unlike to come together, especially if inbreeding is to be avoided. Perhaps the most universal feature of religions around the world and across history have been their celebration of those who have achieved peace and cooperation across difference.

For those with a more practical and quantitative orientation, however, perhaps one of the most compelling bodies of evidence is the finding, popularized by economist Oded Galor in his Journey of Humanity.[5] Building on his work with Quamrul Ashraf charting long-term comparative economic development, he argues that perhaps the most robust and fundamental driver of economic growth is societies' ability to productively and cooperatively harness the potential of social diversity.[6]

While using migratory distance from Africa (where diversity is maximum as noted above) as a proxy for "diversity", Galor and collaborators have since argued that diversity takes a wide range of forms and leads to a broad range of divergent outcomes.[7] Today the word "diversity" is in many contexts used to specify some dimensions along which oppression was historically organized in societies like the US that are particularly culturally dominant in the world today. Yet such a definition is simplistic relative to the tremendous diversity of forms of diversity that define our world:

- Religion and religiosity: A diverse range of religious practices, including secularism, agnosticism, and forms of atheism, are central to the metaphysical, epistemological and ethical perspective of most people around the world.

- Jurisdiction: People are citizens of a range of jurisdictions, including nation states, provinces, cities etc.

- Geographic type: People live in different types of geographic regions: rural v. urban, cosmopolitan v. more traditional cities, differing weather patterns, proximity to geographic features etc.

- Profession: Most people spend a large portion of their lives working and define important parts of their identities by a profession, craft or trade.

- Organizations: People are members of a range of organizations, including their employers, civic associations, professional groups, athletic clubs, online interest groups etc.

- Ethno-linguistics: People speak a range of languages and identify themselves with and/or are identified by others with a "ethnic" groups associated with these linguistic groupings or histories of such linguistic associations, and these are organized by historical linguists into rough phylogenies.

- Race, caste and tribe: Many societies feature cultural groupings based on real or perceived genetic and familial origins that partly shape collective self- and social perceptions, especially given the legacies of severe conflict and oppression based on these traits.

- Ideology: People adopt, implicitly or explicitly, a range of political and social ideologies organized according to schema that themselves differ greatly across social context (e.g. "left" and "right" are key dimensions in some contexts, while religious or national origin divides may be more important in others).

- Education: People have a range of kinds and levels of educational attainment.

- Epistemology/field: Different fields of educational training structure thought. For example, humanists and physical scientists typically approach knowledge differently.

- Gender and sexuality: People differ in physical characteristics associated with reproductive function and in social perception and self-perception associated with these, as well as in their patterns of intimate association connected to these.

- Abilities: People differ greatly in their natural and acquired physical capabilities, intelligence, and challenges.

- Generation: People differ by age and life experiences.

- Species: Nearly all the above has assumed that we are talking exclusively about humans, but some of the technologies we will discuss may be used to facilitate communication and collaboration between humans and other life forms or even the nonbiological natural or spiritual worlds, which is obviously richly diverse internally and from human life.

Furthermore, as we have emphasized repeatedly above, human identities are defined by combinations and intersections of these forms of diversity, rather than their mere accumulations, just as the simple building blocks of DNA's four base pairs give rise to life's manifold diversity.

Yet, if history teaches anything, it is that for all its potential, collaboration across diversity is challenging. Social differences typically create divergences in goals, beliefs, values, solidarities/attachments, and culture/paradigm. Simple differences in beliefs and goals alone are the easiest to overcome by sharing information or agreeing to disagree, many differences in beliefs can be bridged and with common understanding of objective circumstances, compromises on goals are fairly straightforward. Values are more challenging, as they involve things that both sides will be reluctant to compromise over and tolerate.

But the hardest differences to bridge are typically those related to systems of identification (solidarity/attachment) of meaning-making (culture). Solidarity and attachment relate to the others to which one feels allied or sharing in a "community of fate" and interests, groups by which one defines who and what one is. Cultures are systems of meaning-making that allow us to attach significance to otherwise arbitrary symbols. Languages are the simplest example, but all kinds of actions and behaviors carry differing meaning depending on cultural contexts.[8]

Solidarity and culture are so challenging because they stand in the way not of specific agreements about information or goals but of communication, mutual comprehension, and the ability to regard someone else as a partner capable and worthy of such exchange. While they are in an abstract sense related to beliefs and values, solidarities and culture in practice precede these in human development: we are aware of our family and those who will protect us and learn to communicate long before we consciously hold any views or aim for any goals. Being so foundational, they are the hardest to safely adjust or change, usually requiring shared life-shaping experiences or powerful intimacy to reform.

Beyond the difficulty of overcoming difference, it also holds an important peril. Bridging differences for collaboration often erodes them, harnessing their potential but also reducing that potential in the future. While this may be desirable for protection against conflict, it is an important cost to the productive capacity of diversity in the future. The classic illustration is the way that globalization has both brought gains from trade, such as diversifying cuisine, while at the same time arguably homogenizing culture and thus possibly reducing the opportunity for such gains in the future. A critical concern in ⿻ is not just harnessing collaboration across diversity but also regenerating diversity, ensuring that in the process of harnessing diversity it is also replenished by the creation of new forms of social difference. Again, this is analogous to energy systems which must ensure that they not only harvest but also regenerate the sources of their energy to achieve sustainable growth.

The depth-breadth spectrum

Because of the tensions between collaboration and diversity, one would naturally expect a range of approaches that make different trade-offs in terms of depth and breadth. Some aim to allow deep, rich collaboration at the cost of limiting this collaboration to small and/or homogeneous groups. We can think of the "depth" of collaboration roughly in terms of the degree of supermodularity for a fixed set of participants: how much greater is what they create than the sum of what they can create separately, according to the standards of participants. Relationships of love or other deep connection are among the deepest as they allow transformations that are foundational to life, meaning and reproduction that those participating could never have known separately. Superficial, transactional, and often anonymous transactions, as permeate market-based capitalism, on the other hand, brings small gains from trade but nowhere near the depth of connection of intimate love.

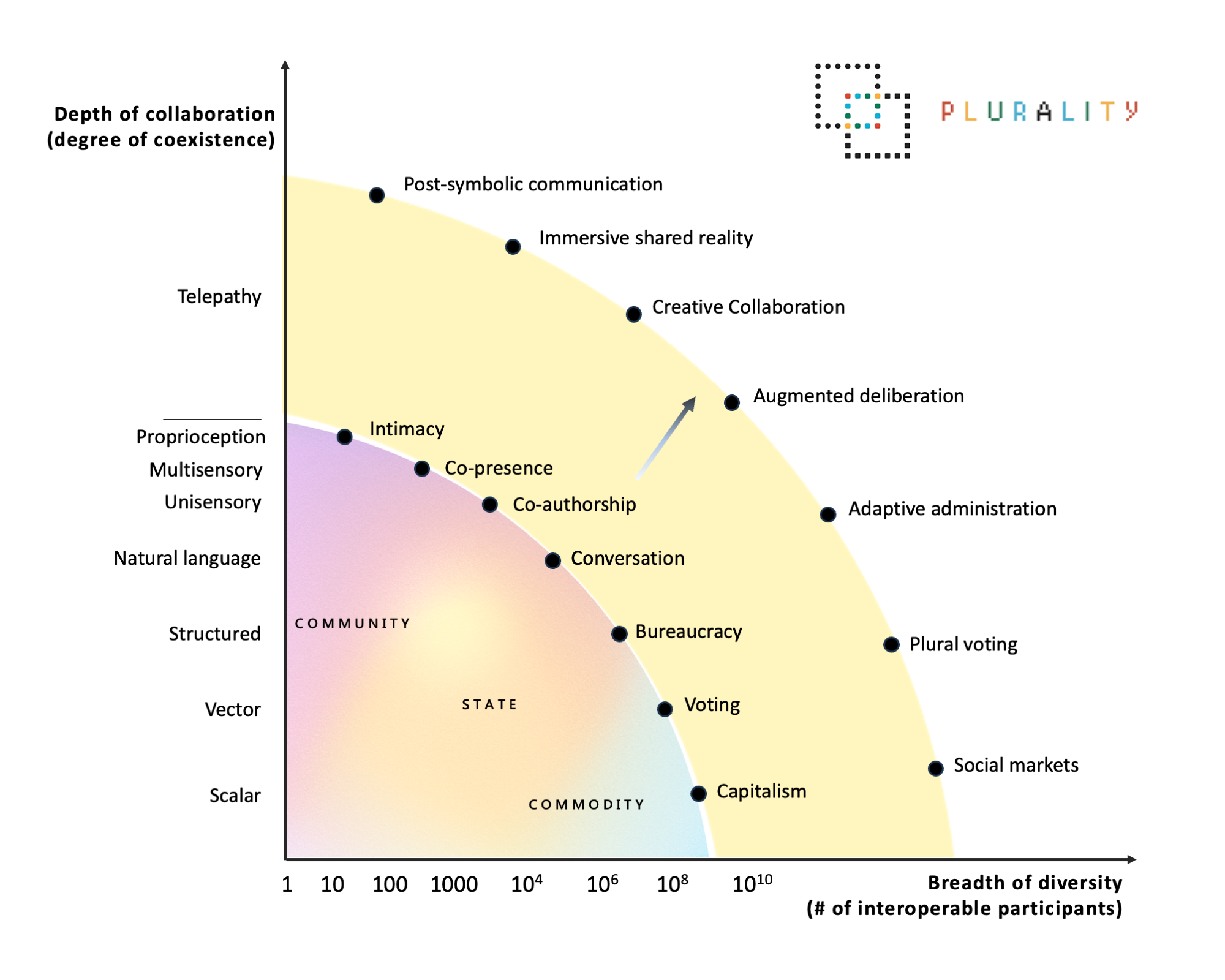

One rough way to think about quantifying the differences between these interaction modes is in terms of the information theoretical concept of bandwidth. Capitalism tends to reduce everything to a single number (scalar) of money. Intimacy, on the other hand, typically not only immerses all senses but goes beyond this to touch "proprioception" (also known as kinesthesia), the internal sensations of one's own body and being that neuroscientists believe constitute a majority of all sensory input.[9] Intermediate modalities lie between, activating structured forms of symbols or limited sets of sense.

The natural trade-off, however, that is the reason capitalism has not been superseded by universal intimacy is that high bandwidth communication is challenging to establish among large and diverse groups. Thinner and shallower collaboration scales more easily. While the simplest notion of scale is the number of people involved, this is shorthand. Breadth is best understood in terms of inclusion across lines of social and cultural distance rather than simply large numbers of people. For example, deep collaboration may well be easier among a large extended family, physically co-located and sharing a language and religion than among a handful of people scattered around the world, speaking different languages, etc.

We can see there being a full spectrum of depth and breadth, representing the trade-off between the two. Economists often describe technologies by "production possibilities frontiers" (PPF) illustrating the currently possible trade-offs between two desirable things that are in tension. In Figure A, we plot this spectrum of cooperation as such a PPF, grouping different specific modalities that we study below into broad categories of "communities" with rich but narrow communication, "states" with intermediate on both and "commodities" with thin but broad cooperative modes. The goal of ⿻ is to push this frontier outward at every point along it, as we have illustrated in these seven points, each becoming a technologically enhanced extension.[10]

One example illustrating this trade-off is common in political science: the debate over the value of deliberation compared to voting in democratic polities. High quality deliberation is traditionally thought to only be feasible in small groups and thus require processes of selection of a small group to represent a larger population such as representative government elections or sortition (choosing participants at random), but is believed to lead to richer collaboration, more complete airing of participant perspectives and therefore better eventual collective choices. On the other hand, voting can involve much larger and more diverse populations at much lower cost but comes at the cost of each participant providing thin signals of their perspectives in the form (usually) of assent for one among a predetermined list of options.

But for all the debate between the proponents of "deliberative" and "electoral" democracy, it is important to note that these are just two points along a spectrum (both mostly within the "state" category) and far from even representing the endpoints of that spectrum. As rich as in-person deliberations can be, they provide nowhere near the depth of sharing, connection and building of common purpose and identity that the building of committed teams (as in e.g. the military) and long-term intimate relationships do. And while voting can allow hundreds of millions to have a say on a decision, it has never cut across social boundaries in any way close to what impersonal, globalized markets do everyday. All these forms have trade-offs and the very diversity of the ways in which we have historically navigated them and the ways in which these have improved overtime (e.g. the advent of video conferencing) should be a source of hope that concerted development can radically improve these trade-offs, allowing richer collaboration across a broader diversity of social differences than in the past.

Goals, affordances and multipolarity

Yet aiming at "improving" this trade-off requires us to specify at least something about what would count as an improvement. What makes a collaboration good or meaningful? What precisely constitutes social difference and diversity? How can we measure both?

One standard perspective, especially in economics and quantitatively inclined fields is to insist that we should specify a global "objective" or "social welfare" function against which progress should be judged. The difficulty, of course, is that, in the face of the limitless possibilities of social life, any attempt to specify such a criterion is destined to crash land on the shores of the unknown and possibly unknowable. The more ambitiously we apply such a criterion in pursuing ⿻, the less robust it will prove, because the more deeply we connect to others across greater difference, the more likely we are to realize the failings of our initial vision of the good. Insisting on specifying such a criterion in advance of learning about the shape of the world leads to premature optimization, which prominent British computer scientist Tony Hoare once labeled "the root of all evil".[11]

One of the worst such evils is papering over the richness and diversity of the world. Perhaps the archetypal example is conclusions about the optimality of markets in neoclassical economics, which depend on extremely simplistic assumptions and have often been used to short-circuit attempts to discover systems for social resource management that deal with problems of increasing returns, sociality, incomplete information, limited rationality, etc. As will become evident in the coming chapters, we know very little about how to even build social systems that are sensitive to these features, much less even approximately optimal in the face of them. This shows why the desire to optimize, chasing some simple notion of the good, often seduces us away from the aspirations of ⿻ as much as it aids us in pursuing it. We can be tempted to maximize what is simple to describe and easy to achieve, rather than anything we are really after.

Optimization, especially in the pursuit of a "social welfare function" carries another pitfall: of "playing God" or idolatry. Maximizing social welfare requires taking a "view from nowhere" and imagining one can influence conditions on a universal level available to no one. We all act from and for specific people and communities, with goals and possibilities limited by who we are, where we sit and who cares what we say, in a network of other forces that hopefully together form a pattern that can avoid disaster. Tools that are only good for some abstractly universal perspectives do not just overreach: they will appeal to no one who can actually adopt them.

At the same time, there is an opposite extreme danger. If we simply pursue designs that imitate features of life and thus engage our attention with little sense of purpose or meaning, we can easily be co-opted to serve the darkest of human motives. The profit motives and power games that organize so much of today's world do not naturally serve any reasonable definition of a common good. The dystopian novels of Neal Stephenson, the Black Mirror series and the predicament of technologist Tunde Martins in the recent Nigerian science fiction show Iwájú remind us of how technical advance decoupled from human values can become traps that fray social bonds and allow the power-hungry to loot, control and enslave us.

Nor do we look to hypothetical scenarios to perceive the danger of compelling technologies pursued without a broader guiding mission. The dominant online platforms of the "Web2" era such as Google, Facebook and Amazon grew precisely out of a mentality of bringing critical features of real-world sociality (viz. collectively determined emergent authority, social networks and commerce) to the digital world. While these services have brought many important benefits to billions of people around the world, we have extensively reviewed above, their many shortcomings and the dangerous path they have brought the world without a broader set of public goals to guide them. We must build tools that serve the felt needs of real, diverse populations, meeting them where they are, and yet we cannot ignore the broader social contexts in which they sit and the conflicts that we might exacerbate in meeting those perceived needs.

Luckily, a middle, pragmatic, ⿻ path is possible. We need neither take a God's eye nor a ground-level view exclusively. Instead, we can build tools that pursue the goals of a range of social groups, from intimate families and friends to large nations, always with an eye to limitations of each perspective and on the parallel developments we must connect to and learn from emanating from other parallel directions of development. We can aim to reform market function by focusing on social welfare, but always doing so based on adding to our models' key features of social richness revealed by those pursuing more granular perspectives and expecting our solutions will at least partly founder on their failures to account for these. We can build rich ways for people to empathize with others' internal experience, but with an understanding that such tools may well be abused if not paired with the discipline of deliberation, regulation and well-structured markets.

We can do this guided by a common principle of cooperation across difference that is too broad to be formulated as a consistent objective function, yet elegant enough to unify a wide range of technologies: we develop tools that allow greater cooperation and consensus at the same time as they make space for greater diversity. Consider two extremely different examples we will discuss below that both can be justified by this logic: brain-to-brain interfaces and approval voting. While the first is a wildly futuristic and disturbingly invasive concept, the second is an old and widely applied voting method. Yet the simple idea of cooperation across difference helps justify both: a key aspiration of brain-to-brain interface is to allow children to retain more of their imagination as they grow to adulthood by allowing them to directly share this imagination rather than having to fit it into what they can write or draw.[12] This allows much greater diversity and much greater common understanding. Similarly, a key goal of approval voting (where citizens can vote for as many candidates as they wish and the one with the most votes wins) is to simultaneously ensure that the elected candidate has very wide general consensus and enable there to exist a much broader diversity of candidates because voters are not afraid a "third party" will act as a spoiler as voters can choose both the third party and one of the leading ones.[13]

Each of these technologies carries its risks: brain-to-brain interfaces could easily be used to manipulate, and approval voting could create a race towards mediocrity, as we discuss in relevant chapters below. Yet the diversity of modes highlighted by this approach gives hope that any connections we make and conflicts we resolve are but one stage in a process of collaboration across diversity. Every successful step forward should bring even more challenging forms of diversity into the world we can perceive, reshaping our understanding of ourselves and our aspirations and demanding that we struggle that much harder to bridge them. While such an aspiration lacks the satisfying simplicity of maximizing an objective function or pursuing technical advance and social richness wherever they lead, this is precisely why it is the hard path worth pursuing. Following another Star Trek slogan, ad astra per aspera: "to the stars, through adversity" or in the words of Nobel laureate André Gide, "Trust those who seek trust, but fear those who have found it."

Regenerating diversity

Yet, as noted above, even if we manage to avoid these pitfalls and successfully bridge and harness diversity, we run the risk, in the process, of depleting the resource diversity provides. This is possible at any point along the spectrum and at any level of technological sophistication. Intimate relationships that form families can homogenize participants, undermining the very sparks of complementarity that ignited love. Building political consensus can undermine the dynamism and creativity of party politics.[14] Translation and language learning can undermine interest in the subtleties of other languages and cultures.

Yet homogenization is not an inevitable outgrowth of bridging, even when one effect is to recombine existing culture and thus lessen their average divides. The reason is that bridging plays a positive, productive role, not just a defensive one. Yes, interdisciplinary bridging of scientific fields may loosen the internal standards of a field and thus the distinctive perspective it brings to bear. But it may also give rise to new, equally distinctive fields. For example, the encounter between psychology and economics has created a new "behavioral economics" field; encounters between biology, physics and computer science have birthed the blossoming field of "systems biology"; the encounter between computer science and statistics has helped launch "data science" and artificial intelligence.

Similar phenomena emerge throughout history. Bridging political divides may lead to excess homogenization, but it can also lead to the birth of new political cleavages. Families often bear children, who diverge from their parents and bring new perspectives. Most artistic and culinary novelty is born of "bricolage" or "fusion" of existing styles.[15] The syntheses that emerge when thesis and antithesis meet are not always compromises, but instead theremay be new perspectives that realign a debate.[16]

None of this is inevitable and of course there are many stories of intersections that undermine diversity. But this range of possibilities gives hope that with careful attention to the issue, it is possible in many cases to design approaches to collaboration that renew the diversity that powers them.

Infinite diversity in infinite combinations

In this part of the book, we will (far from exhaustively) explore a range of approaches to collaboration across difference and how further advances to ⿻ can extend and build on them. Each chapter will begin, as this one did, with an illustration of technology near the cutting edge of what is possible that is in use today. It will then describe the landscape of approaches that are common and emerging in its area. Next it will highlight the promise of future developments that are being researched, as well as risks these tools might pose to ⿻ (such as homogenization) and approaches to mitigating them, including by harnessing tools described in other chapters. We hope that the wide range of approaches we highlight draws out not just the substance of ⿻, but also the consistency of its approach with its substance. Only a ⿻ complementary and networked directions can support the development of a ⿻ future.

Tobin South, Leon Erichsen, Shrey Jain, Petar Maymounkov, Scott Moore and E. Glen Weyl, "Plural Management" (2024) at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4688040. ↩︎

Divya Siddarth, Matt Prewitt and Glen Weyl, "Beyond Public and Private: Collective Provision Under Conditions of Supermodularity" (2024) at https://cip.org/supermodular. ↩︎

David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, (London: John Murray, 1817). ↩︎

The analogy here is even tighter than it might seem at first. What is usually called "energy" is actually "low entropy"; a uniformly hot system has lots of "energy" but this is not actually useful. All systems for producing "energy" work by harnessing this low entropy ("diversity") to produce work; such systems also have the advantage of avoiding "uncontrolled" releases of heat through explosions ("conflict"). There is thus a quite literal and direct analogy between ⿻'s goal of harnessing social low entropy and industrialism's goal of harnessing physical low entropy. ↩︎

Oded Galor, The Journey of Humanity: A New History of Wealth and Inequality with Implications for our Future (New York: Penguin Random House, 2022). ↩︎

Quamrul Ashraf and Oded Galor, "The 'Out of Africa' Hypothesis, Human Genetic Diversity, and Comparative Economic Development", American Economic Review 103, no.1 (2013): 1-46. ↩︎

Oded Galor, Marc Klemp and Daniel Wainstock, "The Impact of the Prehistoric Out of Africa Migration on Cultural Diversity" (2023) at https://www.nber.org/papers/w31274. ↩︎

Lisa Wedeen, "Conceptualizing Culture: Possibilities for Political Science", American Political Science Review 96, no. 4 (2002): 713--728. ↩︎

Uwe Proske and Simon C. Gandevia, "The Proprioceptive Senses: Their Roles in Signaling Body Shape, Body Position and Movement, and Muscle Force", Physiological Review 92, no. 4: 1651-1697. ↩︎

This tripartite division of modes of exchange into communities, state, and commodities is inspired by Kojin Karatani, The Structure of World History: From Modes of Production to Modes of Exchange (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014). Karatani's aspiration to achieve the return of community at a broader scale can be seen as an ambitious example of ⿻. ↩︎

Randall Hyde, "The Fallacy of Premature Optimization" Ubiquity February, 2009 available at https://ubiquity.acm.org/article.cfm?id=1513451. ↩︎

Rajesh P. N. Rao, Andrea Stocco, Matthew Bryan, Devapratim Sarma, Tiffany M. Youngquist ,Joseph Wu and Chantel S. Prat, "A Direct Brain-to-Brain Interface in Humans" PLOS One 9, no. 11: e111322 at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111332. ↩︎

Steven J. Brams and Peter C. Fishburn, "Approval Voting", American Political Science Review 72, no. 3: 831-847. ↩︎

Nancy L. Rosenblum, On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010). ↩︎

Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Elementary Structures of Kinship, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969). ↩︎

This concept is often erroneously attributed to the work of G.W.F. Hegel, but actually originates with Johann Gottlieb Fichte and was not an important part of Hegel's thought. Johann Gottlieb Fichte, "Renzension des Aenesidemus", Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung 11-12 (1794). ↩︎