The Life of a Digital Democracy

The Life of a Digital Democracy

When we see "internet of things,"

let's make it an internet of beings.

When we see "virtual reality,"

let's make it a shared reality.

When we see "machine learning,"

let's make it collaborative learning.

When we see "user experience,"

let's make it about human experience.

When we hear “the singularity is near” —

let us remember: The Plurality is here.

— Audrey Tang, Job Description, 2016

Without living in Taiwan and experiencing it regularly, it is hard to grasp what such an achievement means, and for those living there continuously many of these features are taken for granted. Thus we aim here to provide concrete illustrations and quantitative analyses of what distinguishes Taiwan's digital civic infrastructure from those of most of the rest of the world. Because there are far too many examples to discuss in detail, we have selected six diverse illustrations that roughly cover a primary focal project for each two-year period since 2012; after we briefly list a wide range of other programs.

Illustrations

g0v

More than any other institution, g0v (pronounced gov-zero) symbolizes the civil-society foundation of digital democracy in Taiwan. Founded in 2012 by civic hackers including Kao Chia-liang, g0v arose from discontent with the quality of government digital services and data transparency.[1] Civic hackers began to scrape government websites (usually with the suffix gov.tw) and build alternative formats for data display and interaction for the same website, hosting them at g0v.tw. These "forked" versions of government websites often ended up being more popular, leading some government ministers, like Simon Chang to begin "merging" these designs back into government services.

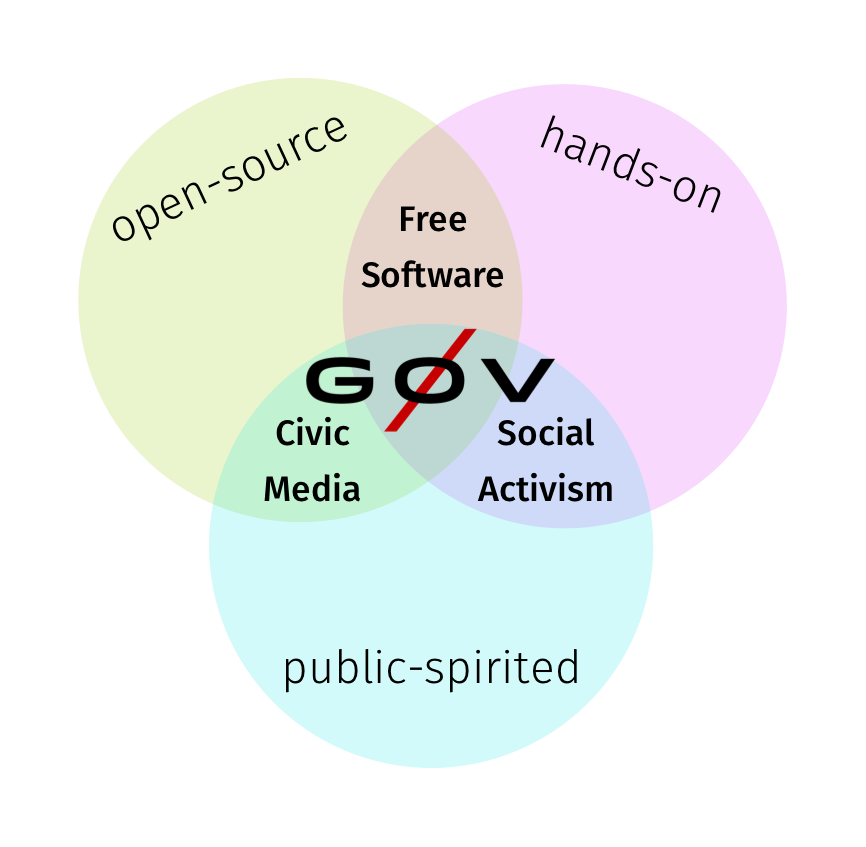

g0v built on this success to establish a vibrant community of civic hackers interacting with a range of non-technical civil society groups at regular hackathon, called "jothons" (based on a Mandarin play on words, meaning roughly "join-athon"). While hackathons are common in many parts of the world, some of the unique features of g0v practices include the diversity of participants (usually a majority non-technical and with nearly full gender parity), the orientation towards civic problems rather than commercial outcomes and the close collaboration with a range of civic organizations. These features are perhaps best summarized by the slogan "Ask not why nobody is doing this. You are the 'nobody'!", which has led the group to be labeled the "nobody movement". They are also reflected in a Venn diagram commonly used to explain the movement's intentions shown in Figure A. As we will note below, a majority of the initiatives we highlight grew out of g0v and closely aligned projects.

Sunflower

While g0v gained significant public attention and support even in its earliest years, it burst most prominently onto the public scene during the Sunflower Movement we described above. Hundreds of contributors in the g0v community were present during the occupation of the Legislative Yuan (LY), aiding in broadcasting, documenting and communicating civic actions. Livestream-based communication sparked heated discussion among the public. Street vendors, lawyers, teachers, and designers rolled up their sleeves to participate in various online and offline actions. Digital tools brought together resources for crowdfunding, rallies, and international voices of support.

On March 30, 2014, half a million people took to the streets in the largest demonstration in Taiwan since the 1980s. Their demands, thus formulated, for a review process prior to the passage of the Cross-Straits Services Trade Agreement was accepted by LY Speaker Wang Jin-pyng on April 6, about three weeks after the start of the occupation, leading to its dispersal soon thereafter. The contributions of g0v to both sides and the resolution of their tensions led the sitting government to see the merit in g0v's methods and in particular cabinet member Jaclyn Tsai recruited one of us as a youth "reverse mentor" and began to attend and support g0v meetings, putting an increasing range of government materials into the public domain through g0v platforms.

Many Sunflower participants devoted themselves to the open government movement; the following local (2014) and general (2016) elections saw a dramatic swing in outcomes of roughly 10 percentage points towards the Green camp, as well as the establishment of a new political party by the Sunflower leaders, the New Power Party, including leading Taiwanese rock star Freddy Lim. Together, these events significantly added to the momentum behind g0v and led to one of our appointment as Minister without Portfolio responsible for open government, social innovation and youth participation.

vTaiwan and Join

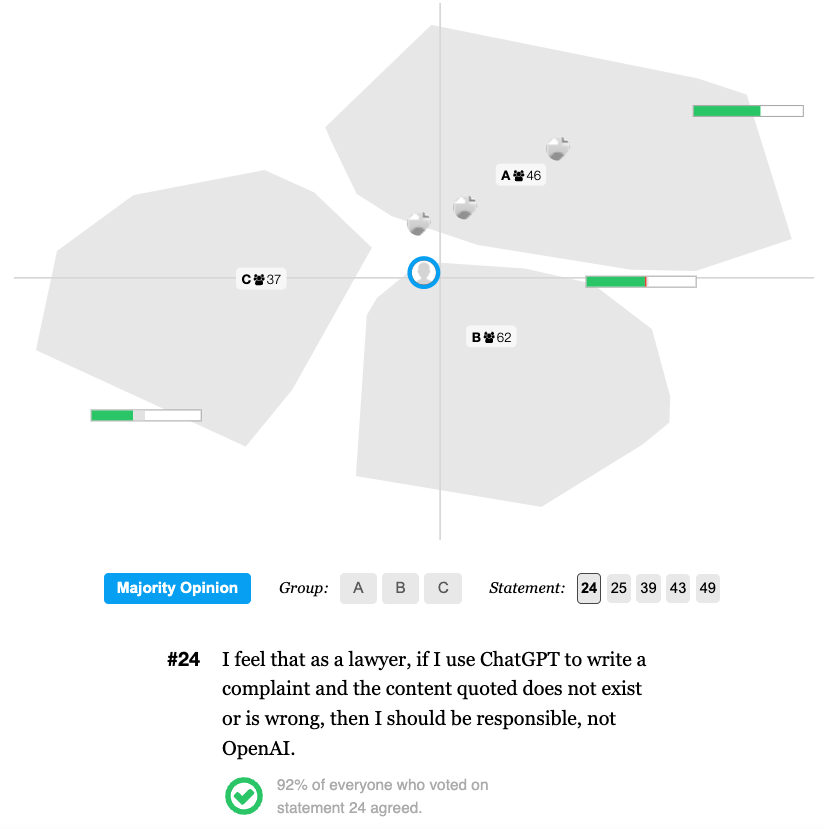

During this process of institutionalization of g0v, there was growing demand to apply the methods that had allowed for these dispute resolutions to a broader range of policy issues. This led to the establishment of vTaiwan, a platform and project developed by g0v for facilitating deliberation on public policy controversies. The process involved many steps (proposal, opinion expression, reflection and legislation) each harnessing a range of open source software tools, but has become best known for its use of the at-the-time(2015)-novel machine learning based open-source "wikisurvey"/social media tool Polis, which we discuss further in our chapter on Augmented Deliberation below. In short, Polis functions similarly to conventional microblogging services like X (formerly Twitter), except that it employs dimension reduction techniques to cluster opinions as shown in Figure B. Instead of displaying content that maximizes engagement, Polis shows the clusters of opinion that exist and highlights statements that bridge them. This approach facilitates both consensus formation and a better understanding of the lines of division.

vTaiwan was deliberately intended as an experimental, high-touch, intensive platform for committed participants. It had about 200,000 users or about 1% of Taiwan's population at its peak and held detailed deliberations on 28 issues, 80% of which led to legislative action. These focused mostly on questions around technology regulation, such as the regulation of ride sharing, responses to non-consensual intimate images, regulatory experimentation with financial technology and regulation of AI.

As a decentralized, citizen-led community, vTaiwan is also a living organism that naturally evolves and adapts as citizen volunteers participate in various ways. The community’s engagement experienced a downturn following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which interrupted face-to-face meetings and led to decreased participation. The platform faced challenges due to the intensive volunteering effort required, the absence of mandates for governmental responses, and its somewhat narrow focus. In response to these challenges, vTaiwan’s community has sought to find a new role between the public and the government and extend its outreach beyond the realm of Taiwanese regulation in recent years. A significant effort to revitalize vTaiwan was its collaboration with OpenAI’s Democratic Input to AI project in 2023. Through partnerships with Chatham House and the organization of several physical and online deliberative events centered on the topic of AI ethics and localization, vTaiwan successfully integrated local perspectives into the global discourse on AI and technology governance. Looking ahead to 2024, vTaiwan plans to engage in deliberations concerning AI-related regulations in Taiwan and beyond. In addition to Polis, vTaiwan is constantly experimenting with new deliberation and voting tools, integrating LLMs for summarization. The vTaiwan community remains committed to democratic experimentation and finding consensus among the public for policymaking. The earlier experience of vTaiwan outside of government also inspired the design of the official Join platform, which is actively used by citizens as a means of proposing issues and ideas to the government.

The Public Digital Innovation Space (PDIS) that one of us established in 2016 to work with vTaiwan and other projects we discuss below in the ministerial role therefore supported a second, related platform Join. While Join also sometimes used Polis, it has a lighter-weight user interface and focuses primarily on soliciting input, suggestions and initiatives from a broader public, and has an enforcement mechanism where government officials must respond if a proposal receives sufficient support. Unlike vTaiwan, furthermore, Join addresses a range of policy issues, including controversial non-technological issues such as high school's start time, and has strong continuing usage today of roughly half of the population over its lifetime and an average of 11,000 unique daily visitors.

Hackathons, coalitions and quadratic signals

While such levels of digital civic engagement may seem surprising to many Westerners, they can be seen simply as the harnessing of a small portion of the energy typically wasted on conflict on (anti-)social media towards solving public problems. Even more concentrated applications of this principle have come by placing the weight of government behind the g0v practice of hackathons through the Presidential Hackathon (PH) and a variety of supporting institutions.

The PH convened mixed teams of civil servants, academics, activists and technologists to propose tools, social practices and collective data custody arrangements that allowed them to "collectively bargain" with their data for cooperation with government and private actors supported by the government-supported program of "data coalitions" to address civic problems. Examples have included the monitoring of air quality and early warning systems for wildfires. Participants and broader citizens were asked to help select the winners using a voting system called Quadratic Voting that allows people to express the extent of their support across a range of projects and that we discuss in our ⿻ Voting chapter below. This allowed a wide range of participants to be at least partial winners, by making it likely everyone would have supported some winner and that if someone felt very strongly in favor of one project they could give it a significant boost. Winning project received a trophy -- a microprojector showing the President of Taiwan giving the award to the winners, leverage they could use to induce relevant government agencies or localities to cooperate in their mission, given the legitimacy g0v has gained as noted above.

More recently, this practice has been extended beyond developing technical solutions to envisioning of alternative futures and production of media content to support this through "ideathons". It has also gone beyond symbolic support to awarding real funding to valued projects (such as around agricultural and food safety inspections) using an extension of Quadratic Voting to Funding as we discuss in our Social Markets chapter.

Pandemic

These diverse approaches to empowering government to more agilely leverage civil participation most dramatically came to a head during the Covid-19 pandemic. Taiwan is widely believed (based on statistics we will discuss in the next section of this chapter) to have had one of the world's most effective responses to the crisis stage of the pandemic. Notably, it achieved among the lowest global death rates from the disease during that stage without using lockdowns and while maintaining among the fastest rates of economic growth in the world. While being an island, having as Taiwan did an epidemiologist ready for an instant response as Vice-President and restricting travel clearly played a key role, a range of technological interventions played an important role as well.

The best documented example and the one most consistent with the previous examples was the "Mask App". Given previous experience with SARS, masks in Taiwan were beginning to run into shortages by late January, when little of the world had even heard of Covid-19. Frustrated, civic hackers led by Howard Wu developed an app that harnessed data that the government, following open and transparent data practices harnessed and reinforced by the g0v movement, to map mask availability. This allowed Taiwan to achieve widespread mask adoption by mid-February, even as mask supplies remained extremely tight given the lack of a global production response at this early stage.

Another critical aspect of the Taiwanese response was the rigorous use of testing, tracing and supported isolation to avoid community spread of the disease. While most tracing occurred by more traditional means, Taiwan was among the only places that was able to reach the prevalence of adoption of phone-based social distancing and tracing systems necessary to make these an important and effective part of their response. This was, in turn, largely because of the close cooperation facilitated by PDIS between government health officials and members of the g0v community deeply concerned about privacy, especially given the lack in Taiwan of an independent privacy protection regime, a point we return to below. This led to the design of systems with strong anonymization and decentralization features that received broad acceptance.

Information integrity

Yet perhaps the single most important digital contributor to Taiwan's pandemic response was its ability to rapidly and effectively respond to misinformation and deliberate attempts to spread disinformation. This "superpower" has extended, however, well beyond the pandemic and been critical to the successful elections Taiwan has held during a time when a lack of information integrity has challenged many other jurisdictions.

Central to those efforts, in turn, has been the g0v spin-off project "Cofacts," in which participating citizens rapidly respond to both trending social media content and to messages from private channels forwarded to a public comment box for requested response. Recent research shows that these systems can typically respond faster, equally accurately and more engagingly to rumors than can professional fact checkers, who are much more bandwidth constrained.[2]

The technical sophistication of Taiwan's civil sector and its support from the public sector have aided in other ways as well. This has allowed organizations like MyGoPen and private sector companies like Gogolook to develop and, with public support, rapidly spread chatbots for private messaging services like Line that make it fast and easy for citizens to anonymously receive rapid responses to possibly misleading information. Government leaders' close cooperation with such civil groups has allowed them to model and thus encourage policies of "humor over rumor" and "fast, fun and fair" responses. For example, when a rumor began to spread during the pandemic that there would be a shortage of toilet paper created by the mass production of masks, Taiwan's Premier Su Tseng-chang famously circulated a picture of himself wagging his rear to indicate it had nothing to fear.

Together these policies have helped Taiwan fight off the "infodemic" without takedowns, just as it fought of the pandemic without lockdowns. This culminated in the January 13, 2024 election we mentioned above, in which a PRC campaign of unprecedented size and AI-fueled sophistication failed to polarize or noticeably sway the election.

Other programs

While these are some of the most prominent examples of Taiwanese digital democratic innovation, there are many other examples we lack the space to discuss in detail but will briefly list here.

- Alignment assemblies: Taiwan has pioneered convening, increasingly common around the world, of citizen participation in the regulation and steering of AI foundation models.

- Information security: Taiwan has become a world leader in the use of distributed storage to guard against malicious content takedowns and of "zero trust" principles in ensuring the security of citizen accounts.

- Gold cards: Taiwan has among the most diversely accessible paths to permanent residence through its "gold card" program, including in a "digital field" to those who have contributed to open source and public interest software.

- Transparency: Building on and extending broader government policies of data transparency, one of us has modeled this idea by making recordings and/or transcripts all of her official meetings public without copyrights.

- Digital competence education: Since 2019, Taiwan has pioneered a 12-Year Basic Education Curriculum that enshrines "tech, info & media literacy" as a core competency, empowering students to become active co-creators and discerning arbiters of media, rather than passive consumers.

- Land and spectrum: Building on the ideas of Henry George, Taiwan has among the most innovative policies in the world to ensure full utilization of natural resources, land and electromagnetic spectrum through taxes that include rights of compulsory sale (as we discuss further in our Property and Contract and Social Markets chapters).

- Participation Officer Network: PDIS helped create a network of civil servants across departments committed to citizen participation, collaboration across government departments and digital feedback, who could act as supporters and conduits of practices such as these.

- Broadband access: Taiwan has one of the most universal internet access rates and has been recognized two years in a row as the fastest average internet in the world.

- Open parliament: Taiwan has become a leader in the global "open parliament" movement, experimenting with a range of ways to make parliamentary procedures transparent to the public and experimenting with innovative voting methods.

- Digital diplomacy: Based on these experiences, Taiwan has become a leading advisor and mentor to democracies around the world confronting similar challenges and with similar ambitions to harness digital tools to improve participation and resilience.

Furthermore, this work sufficiently won the confidence of both the public and the government that in August 2022 Taiwan created a Ministry of Digital Affairs, elevating one of us from Minister without Portfolio to lead this new ministry.

Decade of accomplishment

While this is an interesting set of programs, one might naturally inquire about evidence of their efficacy. Tracing causal impacts precisely for so many projects is obviously an arduous task beyond our scope here. But at very least it is reasonable to ask how Taiwan has performed overall on the range of challenges that has so troubled most liberal democracies in the last decades. We consider each categories of these in turn. Unfortunately, the quality of analysis and comparison possible is not all it could be given the complex geopolitics around Taiwan's international status meaning that many standard international comparators choose not to include it in their data.

Economic

While the economic lens of Taiwan's performance is far from the most important, it is one of the easier to quantify and provides a useful baseline for understanding the starting point for the rest. In one sense, Taiwan is an upper-middle income country, like much of Europe, with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita of $34,000 per person in 2024 according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[3] However, prices are much lower in Taiwan on average than in almost any other rich country; making this adjustment (which economists call "purchasing power parity") makes Taiwan the second richest country on average other than the US with more than 10 million people in the world. Furthermore, as we discuss below, most sources suggest that Taiwan is much more equal than the US, which means it is likely the country of that size with the highest typical living standards in the world. Thus Taiwan is best thought of as among the absolute most developed economies in the world, rather than as a middle-income country.

The sectoral focus of Taiwan's economy stands out as well. While perfectly comparable data are hard to come by, Taiwan is almost certainly the most digital export-intensive economy in the world, with exports of electronics and information and communication products accounting for roughly 31% of the economy, compared to less than half that fraction in other leading technology exporters such as Israel and South Korea.[4] This fact is best known to the world for what it reflects: that most of the world's semiconductors, especially the most advanced ones, are manufactured in Taiwan and Taiwan is also a major both manufacturer and domicile for manufacturers of smartphones such as Foxconn.

Taiwan is also unusual among rich countries in its relatively low tax take; according to the Asia Development Bank, Taiwan collected only 11% of GDP in taxes compared to 34% on average in the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) club of rich countries.[5] Relatedly, Taiwan ranked 4th in the world in the Heritage Foundation's Economic Freedom Index.[6]

Given this background, several features of Taiwan's economic performance in the last decade stand out.

- Growth: Taiwan has averaged real GDP growth of 3% over the last decade, compared to less than 2% for the OECD, a bit over 2% for the US and 2.7% for the world overall.[7]

- Unemployment: Taiwan has averaged an unemployment rate of just under 4% steadily in the last decade, compared to an OECD average of 6%, a US average of 5% and a world average of around 6%.

- Inflation: While inflation has spiked and wildly fluctuated around the world including almost all rich countries, Taiwan's inflation rate has remained relatively steady the last decade in the 0-2% range, averaging 1.3% according to the IMF.

- Inequality: The last decade has seen significant debate about methods in calculating inequality statistics. Using more traditional methods, Taiwan's Survey of Family Income and Expenditure has found that Taiwan's Gini Index of inequality (ranging from 0 for perfectly equal to 1 for perfectly unequal) has been steady at around .28 for the last decade, placing it around the level of Austria on the lower end of global inequality and far lower than the roughly .4 of the US. Other analyses, using innovative but controversial administrative approaches pioneered by economists including Emmanuel Saez, Thomas Piketty, and Gabriel Zucman show Taiwan's top 1% income share at 19%, not far behind the US at 21% and well above a country like France at 13%. However, even in these data, Taiwan's top 1% share has fallen by about a tenth in the last decade, while in both France and the US it has risen by a similar proportion. Furthermore, a number of studies have recently argued these methods tend to find higher inequality in countries and time periods with lower and less progressive taxes as they rely on tax administration data and struggle to fully account for induced avoidance.[8] Given Taiwan's dramatically lower tax take than either the US or France, it seems likely that if these issues apply anywhere, they would lead to a substantial overstatement of Taiwanese inequality.[9]

Putting these facts together, what is notable is that Taiwan's economic performance has been strong and fairly egalitarian or at least not becoming more unequal despite its wealth and extreme tech-intensity. As we documented above, economists have widely blamed the role of technology for many recent economic woes, including slow growth, unemployment and rising inequality. In the world's most tech-intensive economy, this seems not to be the case.

Social

Internationally comparable social indicators are far more difficult than even economic ones for Taiwan, given that it is excluded from the World Health Organization (WHO). However, we were able to find roughly comparable data on two commonly cited social indicators: loneliness and self-reported technology addiction. Loneliness among older adults (above 65) in Taiwan stands at roughly 10%, which puts it around similar rates in the least affected countries in the world (mostly in Northern Europe), better than in North America (roughly 20%) and much better than in the PRC (more than 30%).[10] Another comparison is self reported cellphone addiction rates, which are fairly high in Taiwan (at roughly 28%) but much lower than in the US (at 58%).[11] Differences in rates of addiction to controlled substances are even more dramatically different, with about 10 times as many Americans reporting using illegal drugs at least monthly than Taiwanese who have ever tried an illegal drug.[12]

Taiwan is also marked by a unique experience with religion among rich countries, almost all of which (especially the United States) are both dominated by a single broad religious group (e.g. Christianity) and have seen dramatic declines in a range of measures of religiosity including affiliation and participation in the past decades.[13] Religion in Taiwan, by contrast, is far more diverse with a roughly equal mix of followers of four distinct religious traditions: folk religion, Taoism, Buddhism, Western and minority religions, with about an equal proportion as each of these being non-believers.[14] At the same time, while there has been some shift among these groups, there has hardly been any significant increase in non-belief or non-practicing in Taiwan in the past decades.[15]

Political

Taiwan is widely recognized both for the quality of its democracy and its resilience against technology-driven information manipulation. Several indices, published by organizations such as Freedom House[16], the Economist Intelligence Unit[17], the Bertelsmann Foundation and V-Dem, consistently rank Taiwan as among the freest and most effective democracies on earth.[18] While Taiwan's precise ranking differs across these indices (ranging from first to merely in the top 15%), it nearly always stands out as the strongest democracy in Asia and the strongest democracy younger than 30 years old; even if one includes the wave of post-Soviet democracies immediately before this, almost all are less than half Taiwan's size, typically an order of magnitude smaller. Thus Taiwan is at least regarded as Asia's strongest democracy and the strongest young democracy of reasonable size and by many as the world's absolute strongest. Furthermore, while democracy has generally declined in every region of the world in the last decade according to these indices, Taiwan's democratic scores have substantially increased.

In addition to this overall strength, Taiwan is noted for its resistance to polarization and threats to information integrity. A variety of studies using a range of methodologies have found that Taiwan is one of the least socially, ethnically and religiously polarized developed countries in the world, though some have found a slight upward trend in political polarization since the Sunflower movement.[19] This is especially true in affective polarization, the holding of negative or hostile personal attitudes towards political opponents, with Taiwan consistently among the 5 least affectively polarized countries.[20]

This is despite analyses consistently finding Taiwan to be the jurisdiction targeted for the largest volume of disinformation on earth.[21] One reason for this paradoxical result may be the finding by political scientists Bauer and Wilson that unlike in many other contexts, foreign manipulation fails to exacerbate partisan divides in Taiwan. Instead, it tends to galvanize a unified stance among Taiwanese against external interference.[22]

Legal

Taiwan is consistently ranked as one of the five safest countries in the world and the safest democracy in the world with more than 100,000 people by a very large margin.[23] When one of us first traveled to Taiwan, he was shocked to receive compensation for his flight as a large envelope of cash, which most Taiwanese feel comfortable carrying given the extreme safety. Furthermore, crime in Taiwan continues to trend steadily downward even as countries like the US have seen dramatic surges in especially violent crime.[24] It is worth noting, however, that it has achieved this historically with a fairly strong police presence (somewhat higher than the US) and an incarceration rate that while far short of the US is high by global standards.

Taiwan's legal-political system has also distinguished itself for its ability to adapt to inclusively resolve long-standing social conflicts. In 2017, the Constitutional Court ruled that the government must pass a law to legalize same-sex marriage within two years. After the failure of a referendum on a straightforward same-sex marriage proposal in 2018, the government found a creative way to respond to the interests of all sides. Many who opposed same-sex marriage were concerned that because of traditions of extended families being bound together by marriage, family members opposing the practice could be forced to participate. At the same time, most young people who planned to take advantage of the new provision had more individualistic, partner-based visions of marriage and had no desire to bind their families either, leading the government to pass a legalization bill that exempted kin from the same-sex marriage process.

Existential

Crises come rarely and with low probability. It is thus hard to know how well Taiwan might perform in avoiding or mitigating one. However, perhaps the closest one can reach for is an emergency that did occur: the Covid-19 pandemic. As noted above, Taiwan was widely seen as among the best if not the very best performing country in the world during this episode and here we discuss the quantitative reasons for this esteem.

The exceptional performance that won Taiwan this international acclaim occurred during the focal early stages of the pandemic, during which much of the world was in rolling lockdowns prior to the availability of the vaccine. We can call this the "crisis" stage of the pandemic and declare it to have ended in April 2021, when vaccines were widely available in the US. From the start of the pandemic to April 2021, Taiwan suffered only 12 deaths to the pandemic, giving it by far the lowest death rate to that point of any jurisdiction with estimates considered internationally accurate. Furthermore, Taiwan achieved this without any lockdowns and achieved the fastest economic growth of any rich country bar Ireland in 2020. More broadly, Taiwan's health system has for the better part of a decade been ranked as the world's most efficiently performing by Numbeo, though life expectancy in Taiwan is merely among the highest in the world.[25]

It is important to note, however, that Taiwan performed much less impressively during the "post-crisis" phase following mid-2021, during which vaccine availability and uptake were the most critical components of response and challenges with domestic vaccine production and distribution led to significant loss of life in the coming years. Taiwan still had among the lowest death rates and best economic performance reliably measured by a rich jurisdiction of significant size, but its exceptional leadership early in the pandemic did not fully persist after the crisis phase. This may indicate that the cohesion and civic engagement fostered by crises (like Sunflower and the Pandemic) allow Taiwan to respond more effectively than anywhere in the world, but that additional care and focus is needed to ensure these efforts are institutionalized and sustainable, an important direction for the future we discuss further below.

Another slow-burning crisis that may illustrate this challenge is climate change. While Taiwan has joined many other countries in enshrining its 2050 net zero ambitions into law and has won praise for its plans to reach this goal, its progress thus far has been modest.[26] More broadly, Taiwan has a strong but not outstanding record on environmental protection.[27]

Taiwan nonetheless exhibits unusually high levels of participation and trust in institutions, particularly in its democracy. Voter turnout is among the highest in the world outside countries where voting is compulsory.[28] 91% consider democracy to be at least "fairly good", a sharp contrast to the dramatic declines in recent years in support for democracy even in many long-established democracies.[29]

In short, while like all countries it has key limitations, Taiwan deserves a leading place among global exemplars that it is too rarely afforded. Admiration for Scandinavian countries is a constant refrain on the left in the West, as is praise for Singapore on the right. While all these jurisdictions have important lessons and in fact many important points of overlap with Taiwan, few places offer the breadth of promise in addressing today's leading challenges that Taiwan does and appeal across the typical divides as it does. As an economically free, vibrantly participatory liberal democracy Taiwan both has something to offer all points on the political spectrum of the West and holds arguably the most compelling example available to those looking to leapfrog the practices of increasingly ailing Western democracies. This is especially true given its starting point: without abundant natural resources or strategic position, in a fragile geopolitical setting, with a deeply divided rather than homogeneous and robust sized population and only democratizing a few decades ago, rising from abject poverty in less than a century.

It will doubtless take decades of study to understand the precise causal connections between Taiwan's unique and dramatic digital democratic practices and the range of success it has found in confronting today's most vexing challenges. Yet given this appeal, in the interim, it seems critical to articulate as so many have done for Scandinavia and Singapore, the generalizable philosophy behind the strategies of the world's most admired digital democracy. It is to that task that the rest of this book is devoted.

g0v Manifesto defines it as "a non-partisan, not-for-profit, grassroots movement". MoeDict, an early g0v project, was led by one of the authors of this book. ↩︎

Andy Zhao and Mor Naaman, "Insights from a Comparative Study on the Variety, Velocity, Veracity, and Viability of Crowdsourced and Professional Fact-Checking Services", Journal of Online Trust and Safety 2, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.54501/jots.v2i1.118. ↩︎

“GDP per Capita, Current Prices,” International Monetary Fund, n.d., https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/TWN/CHN. ↩︎

“Exports,” Trading Economics, n.d., https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/exports. ↩︎

“Key Indicators Database,” Asian Development Bank, n.d., https://kidb.adb.org/economies/taipeichina; “Revenue Statistics 2015 - the United States,” OECD, 2015, https://www.oecd.org/tax/revenue-statistics-united-states.pdf. ↩︎

“Index of Economic Freedom.” The Heritage Foundation, 2023. https://www.heritage.org/index/. ↩︎

“GDP Growth (Annual %),” World Bank, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gdp.mktp.kd.zg; “GDP per Capita, Current Prices,” International Monetary Fund, n.d., https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/TWN/CHN. ↩︎

Gerald Auten, and David Splinter, “Income Inequality in the United States: Using Tax Data to Measure Long-Term Trends,” Journal of Political Economy, November 14, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1086/728741. ↩︎

The most interesting statistic we would like to report on is labor's share of income and its trends in Taiwan. However, to our knowledge no persuasive and internationally comparable study of this exists. We hope to see more research on this soon. ↩︎

S. Schroyen, N. Janssen, L. A. Duffner, M. Veenstra, E. Pyrovolaki, E. Salmon, and S. Adam, “Prevalence of Loneliness in Older Adults: A Scoping Review.” Health & Social Care in the Community 2023 (September 14, 2023): e7726692. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/7726692. ↩︎

“More than Half of Teens Admit Phone Addiction .” Taipei Times, February 4, 2020. https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/biz/archives/2020/02/04/2003730302; “Study Finds Nearly 57% of Americans Admit to Being Addicted to Their Phones - CBS Pittsburgh.” CBS News, August 30, 2023. https://www.cbsnews.com/pittsburgh/news/study-finds-nearly-57-of-americans-admit-to-being-addicted-to-their-phones/. ↩︎

“NCDAS: Substance Abuse and Addiction Statistics [2020],” National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics, 2020, https://drugabusestatistics.org/; Ling-Yi Feng, and Jih-Heng Li, “New Psychoactive Substances in Taiwan,” Current Opinion in Psychiatry 33, no. 4 (March 2020): 1, https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000604. ↩︎

Ronald Inglehart, “Giving up on God: The Global Decline of Religion,” Foreign Affairs 99 (2020): 110. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/fora99&div=123&id=&page=. ↩︎

“2022 Report on International Religious Freedom: Taiwan,” American Institute in Taiwan, June 8, 2023, https://www.ait.org.tw/2022-report-on-international-religious-freedom-taiwan/#:~:text=According%20to%20a%20survey%20by. ↩︎

“Religion in Taiwan,” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, January 12, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_Taiwan. ↩︎

“Freedom in the World,” Freedom House, 2023, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world. ↩︎

“Democracy Index 2023,” Economist Intelligence Unit, n.d., https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2023. ↩︎

“Democracy Indices,” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, March 5, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Democracy_indices#:~:text=Democracy%20indices%20are%20quantitative%20and.. ↩︎

Laura Silver, Janell Fetterolf, and Aidan Connaughton, “Diversity and Division in Advanced Economies,” Pew Research Center, October 13, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/10/13/diversity-and-division-in-advanced-economies/.; ↩︎

Andres Reiljan, Diego Garzia, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, and Alexander H. Trechsel. “Patterns of Affective Polarization toward Parties and Leaders across the Democratic World.” American Political Science Review 118, no. 2 (2024): 654–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423000485. ↩︎

Adrian Rauchfleisch, Tzu-Hsuan Tseng, Jo-Ju Kao, and Yi-Ting Liu, “Taiwan’s Public Discourse about Disinformation: The Role of Journalism, Academia, and Politics,” Journalism Practice 17, no. 10 (August 18, 2022): 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2022.2110928. ↩︎

Fin Bauer, and Kimberly Wilson, “Reactions to China-Linked Fake News: Experimental Evidence from Taiwan,” The China Quarterly 249 (March 2022): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S030574102100134X. ↩︎

“Crime Index by Country,” Numbeo, 2023, https://www.numbeo.com/crime/rankings_by_country.jsp. ↩︎

“Taiwan: Crime Rate,” Statista, n.d, https://www.statista.com/statistics/319861/taiwan-crime-rate/#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20around%201%2C139%20crimes. ↩︎

https://www.numbeo.com/health-care/rankings_by_country.jsp ↩︎

“Net Zero Tracker,” Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit, 2023. https://eciu.net/netzerotracker. ↩︎

“2022 EPI Results,” Environmental Performance Index, 2022, https://epi.yale.edu/epi-results/2022/component/epi. ↩︎

Drew DeSilver, “Turnout in U.S. Has Soared in Recent Elections but by Some Measures Still Trails that of Many Other Countries.” Pew Research Center, November 1, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/11/01/turnout-in-u-s-has-soared-in-recent-elections-but-by-some-measures-still-trails-that-of-many-other-countries/. ↩︎

“Taiwan Country Report Report,” BTI Transformation Index, n.d., https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/TWN. ↩︎