Connected Society

Connected Society

Industry and inventions in technology, for example, create means which alter the modes of associated behavior and which radically change the quantity, character and place of impact of their indirect consequences. These changes are extrinsic to political forms which, once established, persist of their own momentum. The new public which is generated remains long inchoate, unorganized, because it cannot use inherited political agencies. The latter, if elaborate and well institutionalized, obstruct the organization of the new public. They prevent that development of new forms of the state which might grow up rapidly were social life more fluid, less precipitated into set political and legal molds. To form itself, the public has to break existing political forms. This is hard to do because these forms are themselves the regular means of instituting change. The public which generated political forms is passing away, but the power and lust of possession remains in the hands of the officers and agencies which the dying public instituted. This is why the change of the form of states is so often effected only by revolution. — John Dewey, The Public and its Problems, 1927[1]

The twentieth century saw as fundamental shifts in social as natural sciences. Henry George, author of the best-selling and most influential book on economics in American and perhaps world history, made his career as a searing critic of private property. Georg Simmel, one of the founders of sociology, originated the idea of the "web" as a critique of the individualist concept of identity. John Dewey, widely considered the greatest philosopher of American democracy, argued that the standard national and state institutions that instantiated the idea hardly scratched the surface of what democracy required. Norbert Wiener coined the term "cybernetics" for a field studying such rich interactive systems. By perceiving the limits of the box of modernity they highlighted even as they helped construct it, these pioneers helped us imagine a social world outside it, pointing the way towards a vision of a Connected Society that harnesses the potential of collaboration across diversity.

Limits of Modernity

Private property. Individual identity and rights. Nation state democracy. These are the foundations of most modern liberal democracies. Yet they rest on fundamentally monist atomist foundations. Individuals are the atoms; the nation state is the whole that connects them. Every citizen is seen as equal and exchangeable in the eyes of the whole, rather than part of a network of relationships that forms the fabric of society and in which any state is just one social grouping. State institutions see direct, unmediated relationships to free and equal individuals, though in some cases federal and other subsidiary (e.g. city, religious or family) institutions intercede.

Three foundational institutions of modern social organization represent this structure most sharply: property, identity and voting. We will illustrate how this works in each context and then turn to the ways that ⿻ social science has challenged and offers ways past the limits of atomist monism.

Property

Simple and familiar forms of private property, with most restrictions and impositions on that right being imposed by governments, are the most common form of ownership in liberal democracies around the world. Most homes are owned by a single individual or family or by a single landlord who rents to another individual or family. Most non-governmental collective ownership takes the form of a standard joint stock company governed by the principle of one-share-one-vote and the maximization of shareholder value. While there are significant restrictions on the rights of private property owners based on community interests, these overwhelmingly take the form of regulations by a small number of governmental levels, such as national, provincial/state and local/city. These practices are in sharp contrast to the property regimes that have prevailed in most human societies throughout most of history, in which individual ownership was rarely absolutely institutionalized and a diversity of "traditional" expectations governed how possessions can rightly be used and exchanged. Such traditional structures were largely erased by modernity and colonialism as they attempted to pattern property into a marketable "commodity", allowing exchange and reuse for a much broad set of purposes than was possible within full social context.[2]

Identity

Prior to modernity, individuals were born into families rooted within kin-based institutions that provided everything, livelihood, sustenance, meaning, and that were for the most part inescapable. No "official documents" were needed or useful as people rarely traveled beyond the boundaries of those they knew well. Such institutions were eroded by the Roman Empire and the spread of Christianity in its wake.[3] As European cities grew in the first centuries of the second millennium of the common era, impersonal pro-sociality of citi-zens began to take shape through the emergence of a diversity of extra-kin social institutions such as monastaries, universities and guilds. Paper-based markers of affiliations with such institutions began to supplant informal kin knowledge. In particular, Church records of baptisms helped lay the foundation for what became the widespread practice of issuing birth certificates. This, in turn, became the foundational document on which essentially all other identification practices are grounded in modern states.[4]

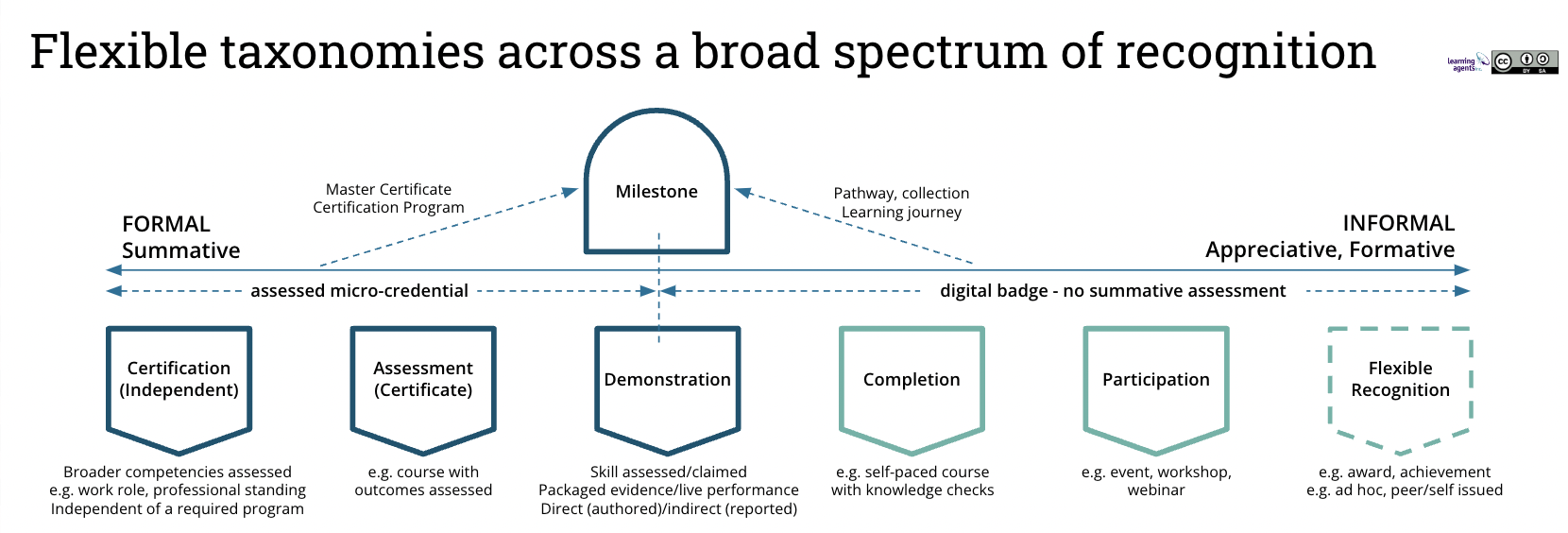

This helped circumvent the reliance on personal relationships, building the foundation of identity in a relationship to a state, which in turn served as a trust anchors for many other types of institutions ranging from children's sports teams to medical care providers. These abstract representations enabled people to navigate the world not based on "who they know" or "where they fit" in a tight social world but as who they are in an abstracted universal sense relative to the state. This "WEIRD" (Western Educated Industrialized Rich Democratic) universalism thus broke with the social embedding of identity while thereby "freeing" people to travel and interact much more broadly using modern forms of identification issued by governments like passports and national identity cards. While other critical credentials, such as educational attainment are more diverse, they almost uniformly conform to a limited structure, implying one of a small number of "degrees" derived from courses with a particular "Carnegie unit" structure (in theory, 120 hours spent with an instructor), in contrast to the broad range of potential recognition that could be given to learning attainment as illustrated in Figure A. In short, just as modernity abstracted ownership private property, removing it from its many social entanglements, it also abstracted personal identity from the social anchoring that limited travel and the formation of new relationships.

Voting

In most liberal democracies, the principle of "one-person-one-vote" is viewed as a sacred core of the democratic process. Of course, various schemes of representation (multi-member proportional representation or single-member districts), checks-and-balances (mutli- v. unicameral legislatures, parliamentary v. presidential) and degrees of federalism vary and recombine in a diverse ways. However both in popular imagination and in formal rules, the idea that numerical majorities (or in some cases supermajorities) should prevail regardless of the social composition of groups is at the core of how democracy is typically understood.[5] Again this contrasts with decision-making structures throughout most of the world and most of history, including ones that involved widespread and diverse representation by a range of social relationships, including family, religious, relationships of fealty, profession, etc.[6] We again see the same pattern repeated: liberal states have "extracted" "individuals" from their social embedding to make them exchangeable, detached citizens of an abstracted national polity.

This regime began to develop during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, when traditional, commons-based property systems, community-based identity and multi-sectoral representation were swept away for the "rationality" and "modernity" of what became the modern state.[7] This system solidified and literally conquered the world during the industrial and colonial nineteenth century and was canonized in the work of Max Weber, reaching its ultimate expression in the "high modernism" of the mid-twentieth century, when properties were further rationalized into regular shapes and sizes, identity documents reinforced with biometrics and one-person-one-vote systems spread to a broad range of organizations.

Governments and organizations around the world adopted these systems for some good reasons. They were simple and thus scalable; they allowed people from very different backgrounds to quickly understand each other and thus interact productively. Where once commons-based property systems inhibited innovation when outsiders and industrialists found it impossible to navigate a thicket of local customs, private property cleared a path to development and trade by reducing those who could inhibit change. Administrators of the social welfare schemes that transformed government in the twentieth century would have struggled to provide broad access to pensions and unemployment benefits without a single, flat, clear database of entitlements. And reaching subtle compromises like those that went into the US Constitution, much less ones rich enough to keep up with the complexity of the modern world, would have likely undermined the possibility of democratic government spreading.

In fact these institutions were core to what allowed modern, wealthy, liberal democracies to rise, flourish and rule, making what Joseph Heinrich calls the "WEIRDest people in the world". Just as the insights of Newtonian mechanics and Euclidean geometry gave those civilizations the physical power to sweep the earth, liberal social institutions gave them the social flexibility to do so. Yet just as the Euclidean-Newtonian worldview turned out to be severely limited and naïve, ⿻ social science was born by highlighting the limits of these atomist monist social systems.

Henry George and the networked value

We remember Karl Marx and Adam Smith more sharply, but the social thinker that may have had the greatest influence during and immediately following his lifetime was Henry George.[8] Author of the for-years best-selling book in English other than the Bible, Progress and Poverty, George inspired or arguably founded many of the most successful political movements and even cultural artifacts of the early twentieth century including:[9]

- the American center-left, as a nearly-successful United Labor candidate for Mayor of New York City;

- the Progressive and social gospel movements, which both traced their names to his work;

- Tridemism, which, as we saw above in our chapter A View from Yushan, had its economic leg firmly founded in Georgism;

- and the game Monopoly, which originated as an educational device "The Landlord's Game", to illustrate how an alternate set of rules could avoid monopoly and enable common prosperity.[10]

George wrote on many topics helping originate, for example, the idea of a secret ballot. But he became most famous for advocating a "single tax" on land, whose value he argued could never properly belong to an individual owner. His most famous illustration asked readers to imagine an open savannah full of beautiful but homogeneous land on which a settler arrives, claiming some arbitrarily chosen large plot for her family. When future settlers arrive, they choose to settle close to the first, so as to enjoy company, divide labor and enjoy shared facilities like schools and wells. As more settlers arrive, they continue to choose to cluster and the value of land rises. In a few generations, the descendants of the first settler find themselves landlords of much of the center of a bustling metropolis, rich beyond imagination, through little effort of their own, simply because a great city was built around them.

The value of their land, George insisted, could not justly belong to that family: it was a collective product that should be taxed away. Such a tax was not only just, it was crucial for economic development, as highlighted especially by later economists including one of the authors of this book. Taxes of this sort, especially when carefully designed as they were in Taiwan, ensure property owners must use their land productively or allow others to do so. The revenue they raise can support shared infrastructure (like those schools and wells) that gives value to the land, an idea called the "Henry George Theorem". We return to all these points in our chapter on Social Markets.

Yet, as attractive as this argument has proven to politicians and intellectuals from Leo Tolstoy to Albert Einstein, in practice it has raised many more questions than it has answered. Simply saying that land does not belong to an individual owner says nothing about who or what it does belong to. The city? The nation state? The world?

Given this is a book about technology, an elegant illustration is the San Francisco Bay Area, where both authors and George himself lived parts of their lives and which has some of the most expensive land in the world. To whom does the enormous value of this land belong?

- Certainly not to the homeowners who simply had the good fortune of seeing the computer industry grow up around them. Then perhaps to the cities in the region? Many reformers have argued these cities, which are in any case fragmented and tend to block development, can hardly take credit for the miraculous increase in land values.

- Perhaps Stanford University and the University of California at Berkeley, to which various scholars have attributed much of the dynamism of Silicon Valley?[11] Certainly these played some role, but it would be strange to attribute the full value of Bay Area land to two universities, especially when these universities succeeded with the financial support of the US government and the collaboration of other universities across the country.

- Perhaps the State of California? Arguably the national defense industry, research complex that created the internet (as we discuss below) and political institutions played a far greater role than anything at the state level.

- Then to the US? But of course the software industry and internet are global phenomena.

- Then to the world in general? Beyond the essential non-existence of a world government that could meaningfully receive and distribute the value of such land, abstracting all land value to such heights is a bit of an abdication: clearly many of the entities above are more relevant than simply "the entire world" to the value of the software industry; if we followed that path, global government would end up managing everything simply by default.

To make matters yet more complex, the revenue earned on the property is but one piece of what it means to own. Legal scholars typically describe property as a bundle of rights: of "usus" (to access the land), "abusus" (to build on or dispose of it) and "fructus" (to profit from it). Who should be able to access the land of the Bay Area under what circumstances? Who should be allowed to build what on it, or to sell exclusive rights to do so to others? Most of these questions were hardly even considered in George's writing, much less settled. In this sense, his work is more a helpful invitation to step beyond the easy answers private property offers, which is perhaps why his enormously influential ideas have only been partly implemented in a small number of (admittedly highly successful) places like Estonia and Taiwan.

The world George invites us to reflect on and imagine how to design for is thus one of ⿻ value, one where a variety of entities, localized at different scales (universities, municipalities, nation states, etc.) all contribute to differing degrees to create value, just as networks of waves and neurons contribute to differing degrees to the probabilities of particles being found in various positions or thoughts occurring in a mind. And for both justice and productivity, property and value should belong, in differing degrees, to these intersecting social circles. In this sense, George was a founder of ⿻ social science.

Georg Simmel and the intersectional (in)dividual

But if network thinking was implicit in George's work, it took another thinker, across the Atlantic, to make it explicit and, accidentally, give it a name. Georg Simmel, pictured in Figure B, was a German philosopher and sociologist of the turn of the twentieth century who pioneered the idea of social networks. The mistranslation of his work as focused on a “web” eventually went “worldwide”. In his 1955 translation of Simmel’s classic 1908 Soziologie, Reinhard Bendix chose to describe Simmel’s idea as describing a “web of group-affiliations” over what he described as the “almost meaningless” direct translation “intersection of social circles”.[12] While the precise lines of influence are hard to trace, it is possible that, had Bendix made an opposite choice, we might talk of the internet in terms of "intersecting global circles" rather than the "world wide web".[13]

Simmel’s “intersectional” theory of identity offered an alternative to both the traditional individualist/atomist (characteristic at the time in sociology with the work of Max Weber and deeply influential on Libertarianism) and collectivist/structuralist (characteristic at the time of the sociology of Émile Durkheim and deeply influential on Technocracy) accounts. From a Simmelian point of view, both appear as extreme reductions/projections of a richer underlying theory.

In his view, humans are deeply social creatures and thus their identities are deeply formed through their social relations. Humans gain crucial aspects of their sense of self, their goals, and their meaning through participation in social, linguistic, and solidaristic groups. In simple societies (e.g., isolated, rural, or tribal), people spend most of their life interacting with the kin groups we described above. This circle comes to (primarily) define their identity collectively, which is why most scholars of simple societies (for example, anthropologist Marshall Sahlins) tend to favor methodological collectivism.[14] However, as we noted above, as societies urbanize social relationships diversify. People work with one circle, worship with another, support political causes with a third, recreate with a fourth, cheer for a sports team with a fifth, identify as discriminated against along with a sixth, and so on. These diverse affiliations together form a person’s identity. The more numerous and diverse these affiliations become, the less likely it is that anyone else shares precisely the same intersection of affiliations.

As this occurs, people come to have, on average, less of their full sense of self in common with those around them at any time; they begin to feel “unique” (to put a positive spin on it) and “isolated/misunderstood” (to put a negative spin on it). This creates a sense of what he called “qualitaitive individuality” that helps explain why social scientists focused on complex urban settings (such as economists) tend to favor methodological individualism. However, ironically as Simmel points out, such “individuation” occurs precisely because and to the extent that the “individual” becomes divided among many loyalties and thus dividual. Thus, while methodological individualism (and what he called the "egalitarian individualism" of nation states we highlighted above that it justfied) takes the “(in)dividual” as the irreducible element of social analysis, Simmel instead suggests that individuals become possible as an emergent property of the complexity and dynamism of modern, urban societies.

Thus the individual that the national identity systems seek to strip away from the shackles of communities actually emerges from their growth, proliferation and intersection. As a truly just and efficient property regime would recognize and account for such networked interdependence, identity systems that truly empower and support modern life would need to mirror its ⿻ structure.

John Dewey's emergent publics

If (in)dividual identity is so fluid and dynamic, surely so too must be the social circles that intersect to constitute it. As Simmel highlights, new social groups are constantly forming, while older ones decline. Three examples he highlights are for his time, the still-recent formations of cross-sectoral 'working men’s associations' representing the general interest of labor, the emerging feminist associations, and the cross-sectoral employers' interest groups. The critical pathway to creating such new circles was the establishment of places (e.g. workman’s halls) or publications (e.g. working men’s newspapers) where this new group could come to know one another and understand, and thus to have things in common they do not have with others in the broader society. Such bonds were strengthened by secrecy, as shared secrets allowed for a distinctive identity and culture, as well as the coordination in a common interest in ways unrecognizable by outsiders.[15] Developing these shared, but hidden, knowledge allows the emerging social circle to act as a collective agent.

In his 1927 work that defined his political philosophy, The Public and its Problems, John Dewey (who we meet in A View from Yushan) considered the political implications and dynamics of these “emergent publics” as he called them.[16]Dewey's views emerged from a series of debates he held, as leader of the "democratic" wing of the progressive movement after his return from China with left-wing technocrat Walter Lippmann, whose 1922 book Public Opinion Dewey considered "the most effective indictment of democracy as currently conceived".[17] In the debate, Dewey sought to redeem democracy while embracing fully Lippmann's critique of existing institutions as ill-suited to an increasingly complex and dynamic wold.

While he acknowledged a range of forces for social dynamism, Dewey focused specifically on the role of technology in creating new forms of interdependence that created the necessity for new publics. Railroads connected people commercially and socially who would never have met. Radio created shared political understanding and action across thousands of miles. Pollution from industry was affecting rivers and urban air. All these technologies resulted from research, the benefits of which spread with little regards for local and national boundaries. The social challenges (e.g. governance railway tariffs, safety standards, and disease propagation; fairness in access to scarce radio) arising from these forms of interdependence are poorly managed by both capitalist markets and preexisting “democratic” governance structures.

Markets fail because these technologies create market power, pervasive externalities (such as "network externalities"), and more generally exhibit “supermodularity” (sometimes called “increasing returns”), where the whole of the (e.g. railroad network) is greater than the sum of its parts; see our chapter on Social Markets. Capitalist enterprises cannot account for all the relevant “spillovers” and to the extent they do, they accumulate market power, raise prices and exclude participants, undermining the value created by increasing returns. Leaving these interdependencies “to the market” thus exacerbates their risks and harms while failing to leverage their potential.

Dewey revered democracy as the most fundamental principle of his career; barely a paragraph can pass without him harkening back to it. He firmly believed that democratic action could address the failings of markets. Yet he saw the limits of existing “democratic” institutions just as severely as those of capitalism. The problem is that existing democratic institutions are not, in Dewey’s view, truly democratic with regards to the emergent challenges created by technology.

In particular, what it means to say an institution is “democratic” is not just that it involves participation and voting. Many oligarchies had these forms, but did not include most citizens and thus were not democratic. Nor would, in Dewey’s mind, a global “democracy” directly managing the affairs of a village count as democratic. Core to true democracy is the idea that the “relevant public”, the set of people whose lives are actually shaped by the phenomenon in question, manage that challenge. Because technology is constantly throwing up new forms of interdependence, which will almost never correspond precisely to existing political boundaries, true democracy requires new publics to constantly emerge and reshape existing jurisdictions.

Furthermore, because new forms of interdependence are not easily perceived by most individuals in their everyday lives, Dewey saw a critical role for what he termed “social science experts” but we might with no more abuse of terminology call “entrepreneurs”, “leaders”, “founders”, “pioneer” or, as we prefer, “mirror”. Just as George Washington's leadership helped the US both perceive itself as a nation and a nation that had to democratically choose its fate after his term in office, the role of such mirrors is to perceive a new form of interdependence (e.g. solidarity among workers, the carbon-to-global-warming chain), explain it to those involved by both word and deed, and thereby empower a new public to come into existence. Historical examples are union leaders, founders of rural electricity cooperatives, and the leaders who founded the United Nations. Once this emergent public is understood, recognized, and empowered to govern the new interdependence, the role of the mirror fades away, just as Washington returned to Mount Vernon.

Thus, as the mirror image of Simmel’s philosophy of (in)dividual identity, Dewey’s conception of democracy and emergent publics is at once profoundly democratic and yet challenges and even overturns our usual conception of democracy. Democracy, in this conception, is not the static system of representation of a nation-state with fixed borders. It is a process even more dynamic than a market, led by a diverse range of entrepreneurial mirrors, who draw upon the ways they are themselves intersections of unresolved social tensions to renew and re-imagine social institutions. Standard institutions of nation state-based voting are to such a process as pale a shadow as Newtonian mechanics is of the underlying quantum and relativistic reality. True democracy must be ⿻ and constantly evolving.

Norbert Wiener's cybernetic society

All of these critiques and directions of thought are suggestive, but none seems to offer clear paths to action and further scientific development. Could the understanding of the ⿻nature of social organization be turned into a scientific engine of new forms of social organization? This hypothesis was the seed from which Norbert Wiener sprouted the modern field of "cybernetics", from which comes all the uses of "cyber" to describe digital technology and, many would argue, the later name of "computer science" given to similar work. Wiener defined cybernetics as "the science of control and communication in (complex systems like) the animal and machine", but perhaps the most broadly accepted meaning is something like the "science of communication within and governance of, by and for networks".[18] The word was drawn from a Greek analogy of a ship directed by the inputs of its many oarsmen.

Wiener's scientific work focused almost exclusively on physical, biological and information systems, investigating the ways that organs and machines can obtain and preserve homeostasis, quantifying information transmission channels and the role they play in achieving such equilibrium and so on. Personally and politically, he was a pacifist, severe critic of capitalism as failing basic principles of cybernetic stabilization and creation of homeostasis and advocate of radically more responsible use and deployment of technology.[19] He despaired that without profound social reform his scientific work would come to worse than nothing, writing in the introduction to Cybernetics, "there are those who hope that the good of a better understanding of man and society which is offered by this new field of work may anticipate and outweigh the incidental contribution we are making to the concentration of power (which is always concentrated, by its very conditions of existence, in the hand of the most unscrupulous. I write in 1947, and I am compelled to say that it is a very slight hope." It is thus unsurprising that Wiener befriended many social scientists and reformers who vested "considerable...hopes...for the social efficacy of whatever new ways of thinking this book may contain."

Yet while he shared the convictions, he believed these hopes to be mostly "false". While he judged such a program as "necessary", he was unable to "believe it possible". He argued that quantum physics had shown the impossibility of precision at the level of particles and therefore that the success of science arose from the fact that we live far above the level of particles, but that our very existence within societies meant that the same principles made social science essentially inherently infeasible. Thus as much as he hoped to offer scientific foundations on which the work of George, Simmel and Dewey could rest, he was skeptical of "exaggerated expectations of their possibilities."

Across all of these authors, we see many common threads. We see appreciation of the ⿻ and layered nature of society, which often shows even greater complexity than other phenomena in the natural sciences: while an electron typically orbits a single atom or molecule, a cell is part of one organism, and a planet orbits one star, in human society each person, and even each organization, is part of multiple intersecting larger entities, often with no single of them being fully inside any other. But how might these advancements in the social sciences translate into similarly more advanced social technologies? This is what we will explore in the next chapter.

John Dewey, The Public and its Problems (New York: Holt Publishers, 1927): p. 81. ↩︎

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1944). ↩︎

Joseph Henrich, The WEIRDest People in the World How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous, (New York Macmillan, 2010). ↩︎

It is worth noting, however, that universal birth registration is a very recent phenomenon and only was achieved in the US in 1940. Universal registration for Social Security Numbers did not even begin until 1987 when Enumeration at Birth was instituted at the federal level in collaboration with county level governments where births are registered. ↩︎

There are, of course, limited exceptions that in many ways prove the rule. The two most notable examples are "degressive proportionality" and "consociationalism". Many federal systems (e.g. the US) apply the principle of degressive proportionality to which we will return later: namely, that smaller sub-units (e.g. provinces in national voting) are over-represented relative to their population. Some countries also have consociational structures in which designated social groups (e.g. religions or political parties) agree to share power in some specified fashion, ensuring that even if one group's vote share declines they retain something of their historical power. Yet these counterexamples are few, far between and usually subjects of on-going controversy, with significant political pressure to "reform" them in the direction of a standard one-person-one-vote direction. ↩︎

David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything (London: Allen Lane, 2021). ↩︎

Andreas Anter, Max Weber's Theory of the Modern State, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). ↩︎

Christopher William England, Land and Liberty: Henry George and the Crafting of Modern Liberalism (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023). ↩︎

Henry George, Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth: The Remedy (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1879) ↩︎

Mary Pilon, The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury and the Scandal Behind the World's Favorite Board Game (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015). ↩︎

AnnaLee Saxenian, The New Argonauts: Regional Advantage in a Global Economy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007). ↩︎

Georg Simmel, Soziologie: Untersuchungen Über Die Formen Der Vergesellschaftung, Prague: e-artnow, 2017. ↩︎

Miloš Broćić, and Daniel Silver, “The Influence of Simmel on American Sociology since 1975,” Annual Review of Sociology 47, no. 1 (July 31, 2021): 87–108, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-090320-033647. ↩︎

Marshall Sahlins, Stone Age Economics (Chicago: Aldine-Atherton, 1972). ↩︎

Georg Simmel, “The Sociology of Secrecy and of Secret Societies,” American Journal of Sociology 11, no. 4 (January 1906): 441–98, https://doi.org/10.1086/211418. ↩︎

John Dewey, op. cit. ↩︎

Robert Westbrook, John Dewey and American Democracy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press). ↩︎

Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics, Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (Paris: Hermann & Cie, 1948). ↩︎

Norbert Wiener, Human Use of Human Beings (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950). ↩︎