What is ⿻?

What is ⿻?

"Action, the only activity that goes on directly between men without the intermediary of things or matter, corresponds to the human condition of plurality, to the fact that men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world." - Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, 1958[1]

"(A)n ideal of 'social connectedness'...denotes a society where bridging ties, across lines of difference are formed at a high rate." - Danielle Allen, "Towards a Connected Society", 2017[2]

"Democracy is a technology. Like any technology, it gets better when more people strive to improve it." - Audrey Tang, Interview with Azeem Azhar, 2020[3]

The increasing tensions between democracy and technology and the way that, starting from such extreme divisions, Taiwan seems to have overcome them naturally raises a question: is there a more broadly applicable lesson on how technology and democracy can interact to be gleaned? We usually think of technology as something that inexorably progresses, while democracy and politics as the static choice between different competing forms of social organization. Taiwan's experience shows us that more options may be available for our technological future, making it more like politics, and that one of these may involve radically enhancing how we live together and collaborate, progressing democracy much like we do technology. It also shows us that while social differences may generate conflict, using appropriate technology, they may also be a fundamental source of progress.

Nor is the possibility of such a direction for technology especially novel. Perhaps the most canonical work of science fiction and thus vision of a positive future is Star Trek, in the original series of which the heroic Vulcans maintain a philosophy of "Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations...a...belief that beauty, growth, progress -- all result from the union of the unlike." Consistent with this idea, we define "⿻ 數位 Plurality", the subject of the rest of this book, briefly as "technology for collaboration across social difference". This contrasts with a common element between Libertarianism and Technocracy: that both consider the world to be made up of atoms (viz. individuals) and a social whole, a view we call "monist atomism". While they take different positions on how much authority should go to each, they miss the core idea of ⿻ 數位 Plurality, that intersecting diverse social groups and the diverse and collaborative people whose identities are constituted by these intersections are the core fabric of the social world.

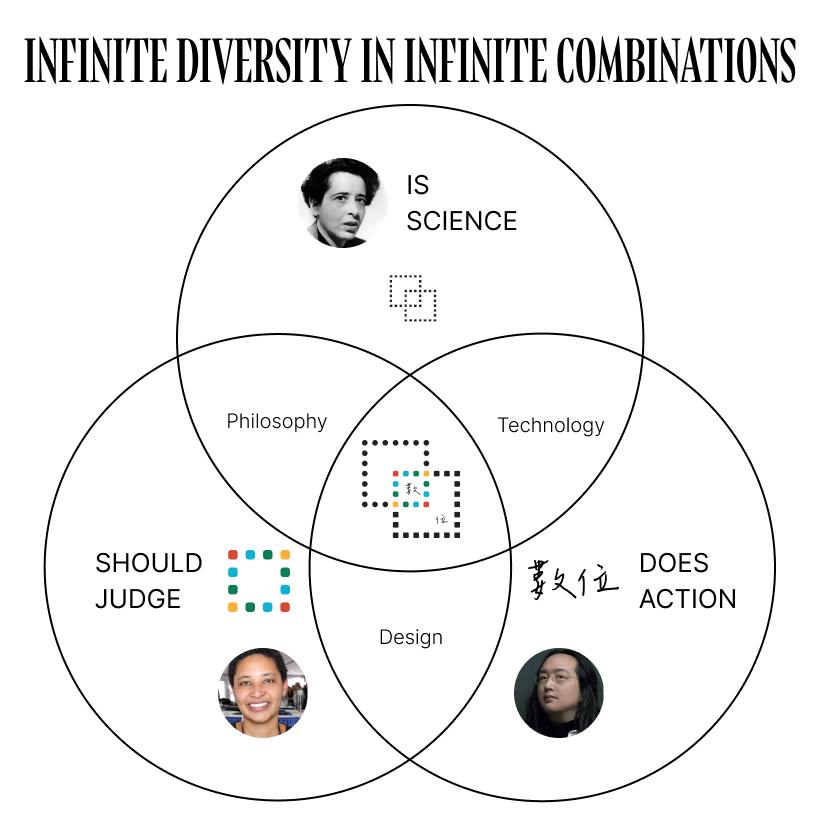

To be more precise, we can break Plurality into three components (descriptive, normative and prescriptive) each associated with one of three thinkers (Hannah Arendt, Danielle Allen and Audrey Tang) each of whom has used the term in these three distinct and yet tightly connected ways, as captured in Figure A above:

- Descriptive: The social world is neither an unorganized collection of isolated individuals nor a monolithic whole. Instead, it is a fabric of diverse and intersecting affiliations that define both our personal identities and our collective organization. We identify this concept with Hannah Arendt and especially her book, The Human Condition, where she labels Plurality as the most fundamental element of the human condition. We identify this descriptive element of Plurality especially with the Universal Coded Character (unicode) ⿻ which captures its emphasis on the intersectional, overlapping nature of identity for both groups and individuals. Furthermore, in the next chapter, Living in a ⿻ World, we highlight that this description applies not merely to human social life, but, according to modern (complexity) science, to essentially all complex phenomena in the natural world.

- Normative: Diversity is the fuel of social progress and while it may explode like any fuel (into conflict), societies succeed largely to the extent they manage to instead harness its potential energy for growth. We identify this concept with philosopher Danielle Allen's ideal of "A Connected Society" and associate it with the rainbow elements that form at the intersection of the squares in the elaborated ⿻ image on the book cover and in the figure above. While Allen has given perhaps the clearest exposition of these ideas, as we explore in The Lost Dao they are deeply rooted in a philosophical tradition including many of the American thinkers who deeply influenced Taiwan, such as Henry George and John Dewey.

- Prescriptive: Digital technology should aspire to build the engines that harness and avoid conflagration of diversity, much as industrial technology built the engines that harnessed physical fuel and contained its explosions. We identify this concept by the use by one of us, beginning in 2016, of the term Plurality to refer to a technological agenda. We associate it even more closely with the use in her title (as Digital Minister) of the traditional Mandarin characters 數位 (pronounced in English as "shuwei") which, in Taiwan, mean simultaneously "plural" when applied to people and "digital" and thus capture the fusion of the philosophy arising in Arendt and Allen with the transformative potential of digital technology. In the last chapter of this section, Technology for Collaborative Diversity, we argue that, while less explicit, this philosophy drove much of the development of what has come to be called the "internet", though because it was not sufficiently articulated it has been somewhat lost since. A primary goal of the rest of the book is to clearly state this vision and thus help it become the alternative it should be to the Libertarian, Technocratic and stagnant democratic stories that dominate much discussion today.

Given this rich definition and the way it blends together elements from traditional Mandarin and various English traditions, throughout the rest of the book we use the Unicode ⿻ to represent this idea set in both noun form (viz. to stand in for "Plurality") and in the adjective form (viz. to stand in for 數位).

In English this may be read in a variety of ways depending on context:

- As "Plurality" typically when used as a concept;[4]

- As "digital", "plural", "shuwei", "digital/plural" or even as a range of other things such as "intersectional", "collaborative" or "networked" when used as an adjective;

None of these existing words perfectly captures this idea set, and thus, in some cases, one might simply say "overlap" or "overlapping" to describe it literally. The rest of the book describes more deeply the content, vision and ambition of ⿻.

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958). ↩︎

Danielle Allen, “Chapter 2: Toward a Connected Society,” in In Our Compelling Interests, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400881260-006. ↩︎

“View Section: 2020-10-07 Interview with Azeem Azhar,” SayIt, https://sayit.pdis.nat.gov.tw/2020-10-07-interview-with-azeem-azhar#s433950, 2020. ↩︎

Note that ⿻ could also be used to represent the closely overlapping meanings of Audrey's interpretations of the two standard variations on the name of her jurisdiction, obviating the need for conflict over ROC v. Taiwan. However, we will leave this observation for someone else to build on given the risk of creating too much ambiguity in the meaning of ⿻. ↩︎